It’s rare that all elements of a production (writing / acting / directing / design)

come together as perfectly as they do in East West Players’ world premiere

production of Jeanne Sakata’s Dawn’s Light: The Journey of Gordon Hirabayashi.

That this production not only engrosses, entertains, and moves an audience but

also educates and informs them as well makes it a must-see.

Gordon Hirabayashi is a little known figure in one of the darkest chapters of

American history, the unjust World War II internment of more than 80,000 United

States citizens (and an additional 40,000 or so U.S. residents), simply because of

their race=Japanese. It was not until decades later that the U.S. government

apologized for this injustice and made financial reparations to surviving internees.

Hirabayashi was a U.S. born citizen in his early twenties when the Japanese

attacked Pearl Harbor. Rather than join his family in an internment camp far from

their Washington home, Hirabayashi, a Quaker, refused to submit to orders that he

considered unconstitutional. Hirabayashi’s case eventually went to the U.S.

Supreme Court which (astounding as it seems) decided unanimously against him.

Award-winning actress Jeanne Sakata was so moved by Hirabayashi’s story that

she set out on an odyssey which led to her writing this amazing one-actor play

about his life. Working together with the brilliant director Jessica Kubzansky and

with Ryun Yu, one of the finest Asian American actors around, Sakata and her

colleagues fashioned a gripping, suspenseful, yet also frequently funny play which

honors Hirabayashi’s battles and celebrates his ultimate victory.

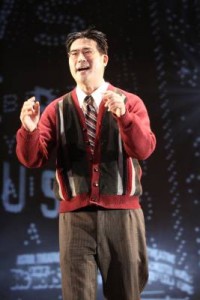

Yu does absolutely stunning work as Gordon. We first see him as an older man,

wearing a bow tie and a too tight sport jacket. Then, as he begins to tell his story,

Yu transforms himself into a young man of another era, hair slicked back, wearing

sweater, necktie, and horned rim glasses, a polite and gentle man for whom

“Jeepers!” was about the strongest swear word in his vocabulary.

We learn of the first moment that Gordon realized that he was “other,” looking at

a friend as they took a bath in his family’s Japanese-style outdoor “ofuro.”

Prejudice against Asian Americans was everywhere. Signs announced “No Japs

allowed,” and once, when Gordon had dared to question what a Caucasian man

had said, he was told by his family, “You must never never again speak that way

to a white man.”

At the University of Washington, Gordon met a cute blonde named Esther

Schmoe (whom he eventually married) while “majoring in extracurricular

activities” and developing a social consciousness. A trip to New York City opened

his eyes to a world without prejudice. Whereas at home his whole life was ruled by

where he could or could not go, in New York there were no bigoted signs on doors.

“I’d finally joined the human race,” Gordon tells us.

When World War II broke out, Gordon felt sure that his family would be protected

by the Unites States Constitution, “because we’re American citizens.” How wrong

he was. “Overnight, our faces had become the faces of the enemy.” Everyone

with 1/16 or more Japanese blood was considered Japanese. Families were forced

to sell all their possessions, leave their homes, and be taken to hot and dusty

camps where they lived behind barbed wire and slept in horses’ stalls.

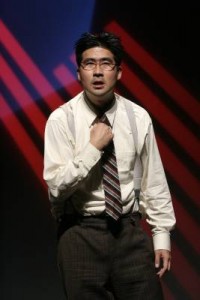

Yu not only portrays Gordon, but the cast of characters who were part of his life,

Yu’s voice changing, taking on various tones and accents. When he speaks

Japanese, his pronunciation is impeccable, as are the various foreign and

American dialects he gives his English speakers. We meet Gordon’s first-generation

parents, his college roommate, the lawyers on both sides of Gordon’s case, as well

as some Hopi Indians he met in jail. In one very amusing sequence (amusing

because of the irony of the situation), Yu becomes the Arizona prison boss who

told Gordon to take in a movie and come back later once they’d located his

missing papers, this after Gordon had hitchhiked down to Arizona to serve his

sentence. (Incredibly, the government—the same government which considered

him a criminal—trusted him to do that!)

Yu’s superb work is clearly a collaboration with director Kubzansky. No actor could

give a 95 minute performance of the caliber of Yu’s without the input, guidance,

and insight of a director of Kubzansky’s imagination and sensitivity. The two had

the advantage of playwright Sakata’s presence as they shaped not only Yu’s

performance but Sakata’s exquisite work itself.

The design team for Dawn’s Light is in a word—magnificent. Maiko Nezu’s set is

deceptively simple, an almost empty stage with two chairs on it, but a sliding

panel halfway upstage works wonders. When slid all the way onto the stage, it

suggests the claustrophobic atmosphere of a jail cell, and when slid completely off

stage, it suggests the openness of the Arizona desert. Nezu’s projection design

utilizes mostly black and white images on the rear wall and sliding panel,

photographs of the era as well as abstract shapes. At times, words are projected

there—the opening lines of the Constitution as the play begins, instructions to

Japanese internees, bigoted anti-Japanese signs, etc. Jeremy Pivnick, whom I

finally had the pleasure to meet, once again proves why he’s in the tiptop echelon

of lighting designers, his work enhancing Nezu’s to the extent that one often

wonders where one’s ends and the other’s begins. Soojin Lee had only one actor

to costume, but she has done so flawlessly, the addition or subtraction of a jacket

or sweater or shirt telling much about where Gordon found himself at each point in

his life.

Finally, there is John Zalewski’s sound design. For some productions, sound design

may mean just the ringing of a phone, or insuring that an orchestra doesn’t

overpower singers. Here, it is as evocative and essential as the set, projection, and

lighting designs. There are the sounds of a Manhattan street, the ticking of a

clock, thunder, news reports, jitterbug music, crickets, night sounds, birds, and eerie

mood setting sounds each perfectly chosen and mixed.

In the final analysis, Dawn’s Light is far more than just a “solo performance.” It is a

beautiful full length play, which happens to require only one actor, but a play

which brings the past vividly alive and which resonates especially strongly in these

days when anyone looking vaguely Middle Eastern can be the victim of “racial

profiling.” Ultimately, it is the powerful and moving story of one man who, in his

own words, “could not give up on the Constitution,” a man who became as much

a hero as any who fought in the war which brought on the crime against

humanity which Gordon Hirabayashi fought so bravely against.

David Henry Hwang Theater, 120 N. Judge John Aiso St., Los Angeles.

–Steven Stanley

November 7, 2007

Photos: Michael Lamont

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY