In the 1990 film Longtime Companion, Craig Lucas wrote what remains

arguably the best dramatic depiction of the epidemic which wiped out much

of an entire generation of gay men. His sensitive screenplay revealed the

goodness and generosity of those 20/30/40something couples whose devotion

was proof that there was much more to gay love than just sex, and that the

gay community was capable of greatness in the face of callous government

disregard.

Five years later, like so many of the characters in Longtime Companion, Lucas

himself became an AIDS widower, and he reacted with justified rage, laying

bare his fury in a column which he wrote for The Advocate magazine entitled

“Postcard From Grief.” Lucas wrote, “Don’t tell me I’m lucky to be alive, to be

HIV-negative. Don’t tell me that life is beautiful. Don’t tell me that I have a lot

to offer. To whom? … Here’s what I understand: people who tear at their flesh

and throw themselves in the grave. People who join monasteries and spend

the rest of their days praying for peace. Terrorists.”

In 1998’s The Dying Gaul*, now being given a first-rate revival at the Elephant

Theatre, much of this anger is evident. This is a play in which none of its three

main players remains guiltless, a play in which all three are capable of deceit,

cruelty, and destruction. Fortunately, in Robert, Jeffrey and Elaine, Lucas

created richly three-dimensional characters who, precisely because they are

essentially good-hearted people, are all the more shocking in their cruelty.

But I get ahead of myself. Here’s the plot in a nutshell.

It is 1995, the year before protease inhibitors transformed AIDS from a death

sentence into a mostly manageable condition. Robert, a writer in his mid-

thirties, has lost his lover Malcolm to AIDS and written a screenplay based on

their life together and Malcolm’s death. Hollywood studio exec Jeffrey is willing

to pay Robert $1,000,000 for the film rights on one condition, that Robert

change Malcolm to Maggie. His reasoning: “Most Americans hate gay people.

If they hear it’s about gay people, they won’t go.” Making the lead couple

heterosexual goes against all of Robert’s principles and his promise to Malcolm,

but seduced by the money, he agrees.

Jeffrey is married with children, but we soon come to realize that he may not

be as devoted to his wife Elaine as Robert was/is to Malcolm. At the end of

their first interview, he hugs Robert and whispers, “You are very handsome.

And I’m getting a little turned on. Are you?”

Soon, the two men are carrying on an affair behind Elaine’s back, though

Jeffrey assures Robert that his wife knows that “I like men,” and as Lucas

himself wrote in “Postcard From Grief,” “(I enjoy) sex of almost any kind–cyber,

phone, video voyeurism, even real and true in-the-flesh sex.” Robert’s sex drive

is as high as ever, if not higher, and with Jeffrey about as hot as they come, it’s

no wonder that Robert allows himself to be seduced.

It is a mention of chat rooms (fairly new in 1995) that sends a fascinated Elaine

to visit the room in which Robert most often chats, and she strikes up a

conversation with him in the guise of a gay man. When Robert lets slip that he

is carrying on an affair with a married man whose wife has become a good

friend, Elaine realizes the truth and sets off on a path whose meanness and

cruelty is shocking, especially from someone who has come across as the kind

of person anyone would be happy to call friend. Her malevolence is nothing,

however, compared to Robert’s in the play’s wallop of a climax. In The Dying

Gaul, no one comes out unscathed.

Please do not let this synopsis scare you away from seeing The Dying Gaul.

Lucas is an amazing writer, and under Jon Lawrence Rivera’s fine direction (is

this man capable of anything less than fine work?), and with a marvelous cast

of four, this is a production which entertains as much as it shocks, and is never

less than involving.

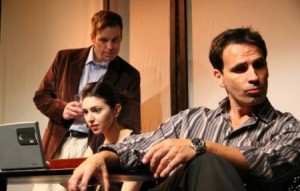

Patrick Hancock, in a diametrically different role from his recent turn as Charley

Brown in Snoopy, is perfectly cast, and perfectly believable as Robert. With his

wide-eyed Midwest likeability and innate sweetness and sincerity, Hancock

immediately wins our sympathy, and opposite the magnetism of darkly

handsome Ken Arquelio as Jeffrey, the sexual chemistry between the two men

is palpable. Completing the trio in their dance of death is the lovely and

winning Mary-Ellen Loukas as Elaine. Loukas, like Hancock, is the kind of actor

whose congeniality immediately wins us over and makes Elaine’s

unpardonable acts somehow still understandable and the character of Elaine

all the more interesting. Still, it is hard to watch the cruel cat and mouse

games she plays with the unsuspecting Robert. Finally, there is the always

splendid Nick Salamone as Dr. Foss, Robert’s therapist, who plays an integral

though unwitting part in Elaine’s deceit.

Each actor has his or her own moments to shine. Watch Hancock’s face

crumble as he realizes that he has chosen money over his principles. Watch

Arquelio as he switches effortlessly from dirty talk (“I want to lick you from head

to toe”) to business when Elaine enters the room. Watch Loukas’ face as her

online chat with Robert turns from sympathy to betrayal as she realizes that

this very nice man has been screwing her husband. Watch Salamone’s subtle

tantrum when Foss finds out that Robert has kept something major from him

for six months.

Lucas’ himself wrote and directed a fine 2005 film version of The Dying Gaul

(starring Peter Sarsgaard as Robert, Campbell Scott as Jeffrey, and Patricia

Clarkson as Elaine) which is an interesting companion piece to the play. For

those who have seen the film, the original theatrical version will be in many

ways a revelation. The play’s Elaine tells us that “I know that Jeffrey likes men

and it’s never threatened us.” The movie’s Elaine seems unaware that her

husband swings both ways. The play’s Elaine is less a villain than the film’s, and

what she does to Robert is less unremittingly evil. Jeffrey’s sexual proclivities are

made more explicit in the play, and heterosexuals in the audience may be

surprised to learn which role Jeffrey prefers when having sex with men. (And

he so tough and macho… Shocking!) One scene from the film is missed—an

intimate sex scene between Robert and Jeffrey which gave Sarsgaard the

kind of tour de force moment that wins acting awards.

The design team assembled here is first rate, with highest marks going to Bob

Blackburn’s sound design with its Taiko drum beats punctuating scene

changes. Gary Lee Reed’s clever set design likewise seems Japanese-inspired,

with its sliding panels. Prop designer Bonnie Bailey Reed somehow got her

hands on “antique” laptops and cell phones. (Amazing how much things

have changed in just 13 years.) Kathi O’Donahue’s lighting is, as always, first-

rate, and Ron Saito’s video design allows us to read Robert and Elaine’s online

chat as the two characters type and speak the words.

My only (small) complaint is that, unlike Lucas’ film, the production loses some

impact in its final moments because the parallels with The Dying Gaul statue*

are not taken advantage of visually. (Those who’ve seen the film can

understand what I’m referring to.)

Other than that tiny quibble, this is L.A. theater at its finest.

* (From Wikipedia.com) is an ancient Roman marble copy of a lost Hellenistic

statue that is thought to have been executed in bronze, which was

commissioned some time between 230 BC and 220 BC by Attalos I of

Pergamon to honor his victory over the Celtic Galatians. The statue depicts a

dying Celt with remarkable realism, particularly in the face, and may have

been painted.[1] He is represented as a Gallic warrior with a typically Gallic

hairstyle and moustache. The figure is naked save for a neck torc. He is shown

fighting against death, refusing to accept his fate.

Elephant Theatre, 6322 Santa Monica Blvd., Los Angeles.

–Steven Stanley

March 22, 2008

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY