Coffee Will Make You Black may seem at first an odd choice for the Celebration, L.A.’s professional theater representing the gay and lesbian community. None of its 18 characters are gay men, and of its many female characters, only a handful may (or then again may not) be lesbian. Hopefully this will not be a turnoff to the Celebration’s loyal core audience, for Coffee Will Make You Black is a joyous, engaging, and laugh-out-loud uproarious celebration of the birth of African American identity in the late 1960s.

Based on April Sinclair’s much-touted bestselling 1995 novel of the same name, and adapted by the Celebration’s Associate Artistic Director Michael A. Shepperd, Coffee Will Make You Black tells the story of Jean Eloise Stevenson, aka Stevie, beginning at age 12, as the gawky, bespectacled preteen begins to discover herself and the changing the world around her.

The play begins with the latest radio news of the Viet Nam War and Stevie’s question “Mama, are you a virgin?” to her incredulous mother. Classmate Michael has asked Stevie the same question, prompting her to do a dictionary search of “virgin.” Discovering that it means, “pure and spotless, like the Virgin Mary,” she informs Michael, “Not exactly.” Not exactly the best thing for the reputation of a good girl like Stevie.

Stickler-for-proper-grammar Mama is not at all pleased when she learns this. “Men are dogs,” she informs her daughter. “Some are just more doggish than others.” Stevie’s sassy, jive-talking friends Neicy and Gail just want to know, “What you guys do? Jus’ play ‘round with your things?” (Clueless Stevie isn’t even sure what that means.)

Women’s roles are as clearly defined in the early 60s as they’d been during the Eisenhower 50s. Though Mama’s job as a bank teller is a bit of an anomaly, still it is Stevie’s brothers who get to sit and watch “the game” with their father while Stevie invariably ends up getting sent out to the store to pick up some ExLax for constipated Papa.

L7 (=square) Stevie’s dream is to be as popular as “all the way cool” Carla, a tough girl whom Stevie has already tangled with over Michael, so when their teacher picks Stevie to perform for Negro History Month, our heroine begs teacher to give her part to Carla. Otherwise, she’ll never get invited to Carla’s birthday party. This impertinence causes a Dr. Jekyll/Mrs. Hyde transformation in the teacher, but wins Stevie Carla’s gratitude, and the sought-after friendship.

Stevie’s excitement about Carla’s getting her first period is not shared by Mama, who declares that “Most people would rather smell dead fish,” prompting Stevie (in one of her many asides to the audience) to remark, “Boy, Mama could sure take the fun out of things.” Mama is of course worried that Stevie will become yet another statistic in a community where many teen girls have become unwed mothers. As Carla’s mom remarks, “Cinderella was not written about the Negro woman.”

At Carla’s party, Stevie discovers at last what it’s like to be popular. At the same time, it’s not cheerleading but playing basketball that interests Stevie. Not a good thing, cautions Carla. Girls who like basketball rather than basketball players get a reputation like Willie Jean, the “funny” butch girl who’s rumored to be “that way.”

Stevie also begins to discover love, first crushing on hottie Yusef. When the object of Stevie’s affection asks to walk her home, Stevie ditches nerdy Roland for the much hunkier Yusef, telling us, “I felt like one of the women who used to be Queen For A Day!”

The world surrounding Stevie begins to change. “You’ll never believe what I just saw on the side of the building,” Mama informs Stevie and her grandma. “‘Black is beautiful.’ I remember when ‘black’ was fighting words. ‘Coffee will make you black,’ that’s what they told white kids to stop them from drinking coffee.”

In the words of Bob Dylan, the times they are indeed a-changin’. Black (not Negro or colored) students are refusing to stand up for The Star Spangled Banner. Dr. Martin Luther King is assassinated. Black people are taking to the streets. And geeky Roland is now in Malcolm X mode, insisting that Stevie sign his “manifesto.”

Stevie begins to look beyond her friendship with Carla. Former classmate Terri, with her elegant permed hair and snooty mother, is back in town and Stevie longs to “get into Charisma.” (I never did quite get what Charisma is, but Stevie sure wants to get in.) Transfer student Sean, a senior(!), asks junior Stevie out on a date. Meanwhile, Stevie develops a crush on the school nurse (a white woman), fantasizing that “she was rescuing me from drowning and giving me mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.”

This, and the suggestion that Nurse Horn may be in a lesbian relationship with a black woman, are about as gay as Coffee Will Make You Black gets. In fact, Nurse Horn tells Stevie that her feelings for her may just be adolescent admiration, merely the proverbial “phase” that gay people are supposedly going through and will grow out of.

Despite Coffee Will Make You Black’s only peripheral connection to the gay community, the production will entertain gays and straights alike, providing they can be convinced to take a chance on it. Shepperd has succeeded in condensing Sinclair’s novel without sacrificing comprehensibility and Nataki Garrett has directed with style and joy.

Though you’ll need to suspend your disbelief more than a bit (the pre-teen/teen characters are all played by actors well into their twenties), the cast couldn’t be better.

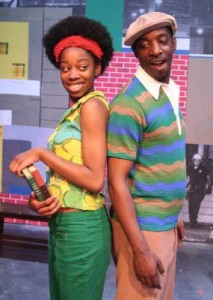

Diona Reasonover is an absolute delight as Stevie, making us care for the ungainly preteen who goes from ugly duckling to Afroed swan. Cecelia Antoinette is a warm and caring (though strict disciplinarian) Mama and Sonia Jackson has many funny moments as Grandma. Aasha Davis and Daniele Watts are both marvelous, having a field day as the lively duo of Neicy and Gail, and Watts gets to do double duty as the snooty Terri. Damani Singleton makes Sean’s transition from dreamboy to dawg believable, and Theodore Perkins is perfectly nerdy as Roland, making his transformation into black activist all the more interesting. Joy Sudduth is very funny as both Stevie’s excitable teacher and Terri’s snobbish mother, though wearing a 60s wig for the latter would help in distinguishing between the two women and better fit Mrs. Cunningham, who insists on straight hair for her daughter but apparently not for herself. Colette Divine is very good in a trio of roles (including dykette Willie Jean) as is Deon Lucas, who plays two. The play’s sole white character, Nurse Horn, is brought to warm and sympathetic life by an excellent Gretchen Koerner. Finally, and possibly best of all, is the scene-stealing work of Charlene Modeste as Carla, who earns a deserved round of applause for her first scene (Carla in tough girl mode), then transitions effortlessly to sassy best friend, and finally shows us a not-so-nice side of Carla as the question of Stevie’s possible sexual orientation comes up.

Marjorie Lockwood’s costumes provide a perfect evocation of the era as does composer/sound designer Ryan Poulson’s original score and choice of 60s hits. Jeffrey Elias Teeter’s inventive lighting design cleverly utilizes the Celebration’s florescent rehearsal lights for classroom scenes. Laura Mroczkowski’s set design consists mainly of a nearly bare stage surrounded by colorful collages of 60s scenes on the Celebration’s four walls. Simple, but it works.

Though Coffee Will Make You Black might seem an odd fit with the Celebration, it is a joyful and laugh-filled delight. Gay audiences may see in Stevie’s “coming out” as a proud black woman their own struggles for self realization, and straight African American audiences (if they can be convinced to visit a gay theater) will either be taken on a nostalgic trip down memory lane, or given a valuable (and never for a moment dull) lesson in contemporary black history.

Celebration Theatre, 7051B Santa Monica Blvd., Hollywood.

–Steven Stanley

April 18, 2008

Photos: Maia Rosenfeld

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY