RECOMMENDED

A 400-year-old slave ship rises out of the Hudson River in front of the Statue of Liberty and all of New York is riveted. As one African-American man swims out to climb atop it, his grandchildren watch from the shore. Many are inspired to think about their lives, and the lives of black people who came before them. No one remains untouched by this miraculous event.

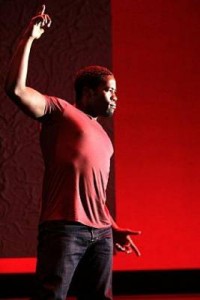

In his one-man show Emergency, writer/actor Daniel Beaty plays all of these characters, giving the kind of performance(s) which inspire(s) words like “brilliant,” “amazing,” “tour de force,” and “you’ll never see better.”

Rightly so. The young African American performer disappears into the skins of 40 different people, male and female, young and old, American and foreign, straight and gay. That these transformations are achieved without costume or makeup changes makes his achievement even more remarkable. Beaty is clearly a talent to be reckoned with, and one we will hear much about in the future.

One of Beaty’s characters writes books on post traumatic slave syndrome. “We have to learn from the Jewish people,” he explains. “They have vowed never to forget.” Another is selling slave ship buttons. A teenager and his sister realize that unlike their non-black classmates, they know little about their people’s history.

Much is revealed about contemporary African American lives in Emergency. One black man is stopped by the police, suspicious that the luxury car he is driving may not be his. (It is.) He fantasizes about shooting them dead. A businessman wishes that people would just “get over it,” this after his white secretary offers to pay him reparations for past wrongs. A tour guide atop the ship talks about the horrors its passengers underwent. Peter, a member of the Harlem Boys Choir, remarks that he sometimes forgets being black, though somehow other people always remember for him. Clarissa, who has AIDS, thinks to herself that maybe she could find a friend aboard the slave ship. Gay poet Rodney describes black people as “walking in an unconscious stage of emergency.”

Beaty is also a singer, and a sensational one at that, performing several of his original songs and a sublime a cappella Amazing Grace.

Emergency is at its best when its characters speak in their everyday voices, with Beaty’s facial expressions, body language, and vocal patterns undergoing a complete transformation every time he becomes someone new.

Less engrossing for me were the frequent “slam poetry” segments, centered around a fanciful TV show entitled “America’s Next Top Poet” and hosted by the glamorous “Sharita.” Though technically brilliant (animated silhouettes projected behind Beaty match his body movements to perfection), I found myself tuning out each time a contestant began to poeticize. I realize that this may be a minority reaction (no pun intended) from someone who doesn’t particularly respond to poetry. Many will surely be enraptured by these segments, and Beaty’s abilities as a slam poet. I myself would have preferred to spend more time just hearing the characters speak in their everyday words.

Every solo performance production is a collaboration between actor and director, and it is certain that director Charles Randolph-Wright must share in the credit for Beaty’s stellar work. Edward E. Haynes, Jr.’s set design is deceptively simple but effective in its use of sliding panels. Michael Gilliam’s lighting is striking, as is Cricket S. Myers’ sound design. Adding greatly to the production’s effectiveness are Alexander V. Nichols’ projection design and Kathryn Bostic’s original music.

The fact that Beaty’s words inspired a standing ovation from Saturday’s almost entirely white audience is proof of Emergency’s universality. Hopefully, reviews and word-of-mouth will reach the African American community, whose response is sure to be even stronger and more personal.

Geffen Playhouse, 10886 Le Conte Ave., Westwood.

–Steven Stanley

April 26, 2008

Photos: Michael Lamont

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY