What a difference a director makes.

When I saw a production of Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit last April, I just didn’t get it. The bizarre costuming and makeup (the lead actor wore green glitter in his gelled jet black hair, dark glittery lipstick, heavy eye shadow, and rouge, and was attired in a waistcoat, dark green silk vest, tight black leggings and 8” platform boots) and robotic movements affected by the actors took me out of the story and not into the world they were striving to create.

Thus, I approached San Diego’s Diversionary Theatre production of No Exit with a teensy bit of trepidation.

Happily, in the assured hands of award-winning director Esther Emery, and performed by a sterling cast of four, this is a No Exit which works absolutely. It entertains, it captivates, and it provokes thought.

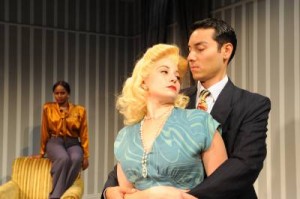

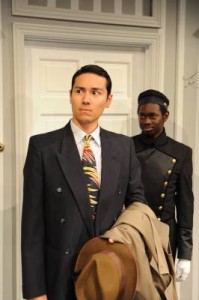

Jennifer Brawn Gittings’ gorgeous costumes place No Exit smack dab in the middle of the 1940s, which is when Sartre’s 1945 one-act play takes place. Jungah Han’s imaginative set design takes us to a monochromatic hell-as-a-living room (grey and white striped walls, and drapes which part to reveal … the wall) bathed in Jason Bieber’s stark white lighting.

No Exit’s most quoted line is “L’enfer, c’est les autres,” or as translated here by Paul Bowles, “Hell is just–other people,” and over the course of an hour and a half, No Exit’s three main characters (the forth is a bellboy who appears only in the play’s opening scene) make each other’s lives a living (though often very amusing) hell.

First to arrive is Cradeau, a cheat, an Army deserter, and a coward who motivated the suicide of his wife after his death by firing squad. He is then joined by lesbian seductress/murderess Inez and finally by Estelle, who married for money and cheated on her husband with a younger man, then killed her infant child, driving her lover to suicide.

Lovely people … not. But fun to watch? Most assuredly yes.

Emery’s cast get all the laughs that existentialist Sartre most certainly intended (no dull philosopher this one). The bellboy asks Cradeau, “Why in hell would you want to brush your teeth here?” Estelle expresses dismay at having to sit on an inappropriately-hued divan. “I’m in turqouise and it’s upholstered in spinach green,” she pouts. When Estelle asks Inez if she prefers men jacketed or in shirtsleeves, Inez responds flatly, “Shirts or no shirts, I’m not very fond of men anyway.” (Big laugh from the lesbians in attendance.)

But all is quite definitely not fun and games in Sartre’s world, as when Inez tells Estelle, “We’re all in this together. Criminals together. We’re in hell. Damned. People suffered, they went through agonies because of us. It’s got to be paid for now.” It’s also Inez who first expresses Sarte’s “L’enfer c’est les autres,” when she realizes that “each one of us is the torturer for the other two.” And later, much later, when Inez is forced to watch a passionate kiss between Cradeau and Estelle, she informs them, “Go on, make your love, make love. But this is Hell, and you’ll get your turn to suffer.”

In the Existentialist Gospel According To Sartre, the meaning of an individual’s life is not established until his or her existence begins. No wonder Estelle is upset to discover that there are no mirrors in hell. “When I can’t see myself in the mirror,” she explains, “I can’t even feel myself, and I begin to wonder if I really exist at all.”

1940s Sartre was well ahead of his time in his depiction of an unapologetic lesbian character (“I was what they call back there, one of those women.”), who knew what she wanted (another man’s wife) and did what needed to be done to get her (and get rid of him in the process).

As Cradeau, an excellent Steven Lone is handsome and dashing enough to turn any woman’s head (or as the is the Diversionary, any man’s), and it’s fun to see him react in shock to Inez’s lack of interest, this man who is most definitely not used to women not falling under his charms. Monique Gaffney is a deliciously cold-as-ice Inez, with a stare that could freeze hell. (There’s a great lesbian moment when Inez blots Estelle’s lipstick with her finger, then licks it.) The divine Rhianna Basore plays Estelle as a flighty, coquettish blonde who can tell Inez in a sweetly deadpan voice, “You’re a little terrifying.” All three lead performances are pitch perfect, stylized and heightened just enough to suit Sartre’s language (as translated from the French by Bowles) and yet rooted in reality. In the much smaller role of the Bellboy, Kevin Morrison is slyly insinuating, and very funny indeed. (Kudos to Missy Bradstreet for her 1940s hair design, and especially for Estelle’s just a bit over the top blonde wig.)

As part of the LGBT Diversionary’s season, No Exit will be a draw for the lesbian community, Sartre having been considerably ahead of his time in making Inez a woman who desired other women. Sartre’s deliciously clever humor has a sensibility about it that gay men in the audience will respond to. Philosophy, literature, and French aficionados will want to see No Exit for its dramatization of Sartre’s Existentialist ideas. In fact, there’s something for every theater lover in this production, which pays Sartre his due respect without ever becoming academic or dull. No one in the audience is likely to be looking for the exit while the lights are up on No Exit.

Diversionary Theatre, 4545 Park Blvd., San Diego. Through October 5. Thursdays at 7:30, Fridays and Saturdays at 8:00, Sundays at 2:00 and 7:00. Monday September 22 at 7:30. Tickets: 619-220-0097 or www.diversionary.org.

–Steven Stanley

September 12, 2008

Photos: Ken JacquesWhat a difference a director makes.

When I saw a production of Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit last April, I just didn’t get it. The bizarre costuming and makeup (the lead actor wore green glitter in his gelled jet black hair, dark glittery lipstick, heavy eye shadow, and rouge, and was attired in a waistcoat, dark green silk vest, tight black leggings and 8” platform boots) and robotic movements affected by the actors took me out of the story and not into the world they were striving to create.

Thus, I approached San Diego’s Diversionary Theatre production of No Exit with a teensy bit of trepidation.

Happily, in the assured hands of award-winning director Esther Emery, and performed by a sterling cast of four, this is a No Exit which works absolutely. It entertains, it captivates, and it provokes thought.

Jennifer Brawn Gittings’ gorgeous costumes place No Exit smack dab in the middle of the 1940s, which is when Sartre’s 1945 one-act play takes place. Jungah Han’s imaginative set design takes us to a monochromatic hell-as-a-living room (grey and white striped walls, and drapes which part to reveal … the wall) bathed in Jason Bieber’s stark white lighting.

No Exit’s most quoted line is “L’enfer, c’est les autres,” or as translated here by Paul Bowles, “Hell is just–other people,” and over the course of an hour and a half, No Exit’s three main characters (the forth is a bellboy who appears only in the play’s opening scene) make each other’s lives a living (though often very amusing) hell.

First to arrive is Cradeau, a cheat, an Army deserter, and a coward who motivated the suicide of his wife after his death by firing squad. He is then joined by lesbian seductress/murderess Inez and finally by Estelle, who married for money and cheated on her husband with a younger man, then killed her infant child, driving her lover to suicide.

Lovely people … not. But fun to watch? Most assuredly yes.

Emery’s cast get all the laughs that existentialist Sartre most certainly intended (no dull philosopher this one). The bellboy asks Cradeau, “Why in hell would you want to brush your teeth here?” Estelle expresses dismay at having to sit on an inappropriately-hued divan. “I’m in turqouise and it’s upholstered in spinach green,” she pouts. When Estelle asks Inez if she prefers men jacketed or in shirtsleeves, Inez responds flatly, “Shirts or no shirts, I’m not very fond of men anyway.” (Big laugh from the lesbians in attendance.)

But all is quite definitely not fun and games in Sartre’s world, as when Inez tells Estelle, “We’re all in this together. Criminals together. We’re in hell. Damned. People suffered, they went through agonies because of us. It’s got to be paid for now.” It’s also Inez who first expresses Sarte’s “L’enfer c’est les autres,” when she realizes that “each one of us is the torturer for the other two.” And later, much later, when Inez is forced to watch a passionate kiss between Cradeau and Estelle, she informs them, “Go on, make your love, make love. But this is Hell, and you’ll get your turn to suffer.”

In the Existentialist Gospel According To Sartre, the meaning of an individual’s life is not established until his or her existence begins. No wonder Estelle is upset to discover that there are no mirrors in hell. “When I can’t see myself in the mirror,” she explains, “I can’t even feel myself, and I begin to wonder if I really exist at all.”

1940s Sartre was well ahead of his time in his depiction of an unapologetic lesbian character (“I was what they call back there, one of those women.”), who knew what she wanted (another man’s wife) and did what needed to be done to get her (and get rid of him in the process).

As Cradeau, an excellent Steven Lone is handsome and dashing enough to turn any woman’s head (or as the is the Diversionary, any man’s), and it’s fun to see him react in shock to Inez’s lack of interest, this man who is most definitely not used to women not falling under his charms. Monique Gaffney is a deliciously cold-as-ice Inez, with a stare that could freeze hell. (There’s a great lesbian moment when Inez blots Estelle’s lipstick with her finger, then licks it.) The divine Rhianna Basore plays Estelle as a flighty, coquettish blonde who can tell Inez in a sweetly deadpan voice, “You’re a little terrifying.” All three lead performances are pitch perfect, stylized and heightened just enough to suit Sartre’s language (as translated from the French by Bowles) and yet rooted in reality. In the much smaller role of the Bellboy, Kevin Morrison is slyly insinuating, and very funny indeed. (Kudos to Missy Bradstreet for her 1940s hair design, and especially for Estelle’s just a bit over the top blonde wig.)

As part of the LGBT Diversionary’s season, No Exit will be a draw for the lesbian community, Sartre having been considerably ahead of his time in making Inez a woman who desired other women. Sartre’s deliciously clever humor has a sensibility about it that gay men in the audience will respond to. Philosophy, literature, and French aficionados will want to see No Exit for its dramatization of Sartre’s Existentialist ideas. In fact, there’s something for every theater lover in this production, which pays Sartre his due respect without ever becoming academic or dull. No one in the audience is likely to be looking for the exit while the lights are up on No Exit.

Diversionary Theatre, 4545 Park Blvd., San Diego.

www.diversionary.org

–Steven Stanley

September 12, 2008

Photos: Ken Jacques

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY