Those who adhere to strict standards of political correctness should not, I repeat NOT see Shanghai Moon, Charles Busch’s spoof of the “Oriental” melodramas of Hollywood’s Golden Era. All others will have a devilishly good time reliving the forbidden passions of such “classics” as Lady From Chungking, Daughter Of Shanghai, King Of Chinatown, Shanghai Express, and Daughter Of The Dragon, all of them starring the immortal Anna May Wong. After all, as the program cover states, “There is enchantment when East meets West under the Shanghai Moon.”

As our “drama” begins in 1931 Shanghai, the household of Chinese warlord General Gong Fei (Christopher Chen) is all abuzz with the impending arrival of British Consul Lord St. John Allington (Michael Gregory), and his much younger wife Lady Sylvia (playwright Busch himself in the original and the next best thing to Busch himself, R. Christofer Sands, here). Mah Li (Amanda Sevold), the General’s beautiful and inscrutable mistress (What? You expected her to be scrutible?) is worried. She has consulted the stars and determined that Lady Allington was “born under sign of Taurus the bull with ties to both Aries and Leo. The effect is turbulent, selfish and bitchy.” The General is more concerned about the flower arrangement “in guest powder room. The inclusion of daffodil signifies ‘Leave Shanghai, you ugly twat.’ That is not message I prefer to give to Lady Allington.”

The Consul has sent ahead a gift, a framed painting of a reclining Lady Allington, naked as the day she was born and surrounded by Russian wolfhounds (with a small puppy nuzzling her breast). General Gong Fei sees “mystery in eyes, sadness, pain,” to which Mah Li replies, “I see squinty eyes and mean little mouth.” Clearly there is also going to be trouble when East meets West, or at least when Mah Li meets Lady Sylvia.

Soon enough, the General is welcoming Lord and Lady Allington to the “House of Thirty-Seven Pansies,” the elegantly dressed and coiffed Lady Sylvia expressing relief that her painting does not class with his “chinoiserie.” “I’m simply mad for orientalia,” she confesses. She is less mad about her elderly husband’s many ailments, including “gout, dyspepsia, thrombosis, sciatica and a permanent sinus.” He also “suffers from an enlarged bowel, which causes chronic flatulence.” (Be prepared.)

With a husband old enough to be her father, no wonder Lady Sylvia is attracted to the virile General. The General too has grown bored with Mah Li, whom he found “languishing in noodle factory in Chalpei.”

Lord Allington expresses his interest in one of General Gong Fei’s treasures, the jade bust of the Empress Heng Lu, which like all of the General’s possessions has the imprint of a chrysanthemum on its base. “It is a brand that I burn onto the bottom of all my possessions,” explains the General, and adds, “There are times when a brand can enhance a bare bottom.” (A prophetic statement if there ever was one.)

As the action of Shanghai Moon progresses, its plot thickens with the arrival of Mrs. Paula Carroll (Sarah Lilly), madam of a brother with Chinese boys and girls under the age of fifteen, and Pug Talbot, a blackmailing “pirate for hire” (and portrayed by statuesque Minda Grace Ware in male drag). There is also Dr. Wu (Dale Sandlin), General Gong Fei’s ancient, hunchbacked physician, and later on a pair of British barristers (played by Lilly and Sandlin).

We learn of Lady Sylvia’s shades-of-Blanche-Dubois liaison with beautiful, sensitive 18-year-old Boy Barclay, and later of her less than blue-blooded upbringing in Chicago on “a steady diet of kielbasa and bitterness.” “I know what it’s like to be snubbed and spat on!” she confesses, and then reveals the secret of her rise to high society: “I knew that success was made in the boudoir.”

As may be gathered from the above quotes, plot plays second fiddle to dialog in a Busch play, and under Ken Salzman’s pitch perfect direction, the entire cast delivers Busch’s lines (and his double entendres) with just the right blend of “serious acting” and “serious overacting,” the combination of which proves irresistible.

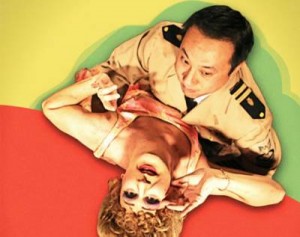

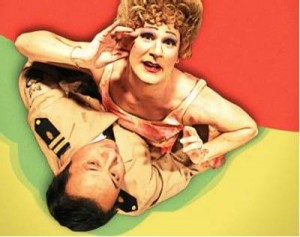

The key to the success of a Charles Busch play is the actor who assumes the leading lady role originated by Busch himself, and there is no one who does this better than Sands. Like Busch, Sands pays loving tribute to the glamorous screen goddesses of the Golden Age of Hollywood. There is a bit of Bette, a dash of Joan, a smidgen of Garson, a soupçon of Colbert, and a taste of Hayward in Sands’ Lady Sylvia, “a loose and wanton woman … painted with sin and cheap pancake makeup.” Sands’ gorgeous countertenor voice, which won him the Ovation Award for Best Actor in a Musical, is featured in a musical number added especially for this production, and the divalicious actor gets to chew scenery with the best of Hollywood’s first ladies when a few puffs on the General’s opium pipe sends Lady Sylvia into tremors, and again later in a deliciously over-the-top courtroom confession.

Chen proves the perfect macho complement to Sands, affectionately lampooning every “oriental” male stereotype in the book save one. (Her arms and legs wrapped around the General, Lady Sylvia tells him, “You certainly put the kibosh on that stereotype of Oriental men.”) As Mah Li (the Anna May Wong role), Sevold’s bowed head and sing-song voice are about as politically incorrect as imaginable, but beautifully underplayed (and if you’re wondering why the role is not being played by an Asian actress, there’s a very good reason which won’t be revealed here). Sandlin’s philosophic Dr. Wu gets laughs every time he opens his mouth. The “occidentals” are equally well represented by Gregory as the doddering Lord St. John (pronounced Sinjin), Lilly as the feisty Mrs. Carroll, and Ware as a macho Pug. Lilly and Sandlin also double amusingly as Sir Lionel Wescott and Sir Geoffrey Finch in the courtroom finale.

David Calhoun deserves highest marks for his beautifully appointed set design straight out of a 1930s “oriental” melodrama as does Maro Parian for the show’s splendid costumes, from the Asian characters’ Chinese silks to Sands’ elegant high society gowns. SanZman’s sound design incorporates appropriately melodramatic background music. Henrik Mansourian’s lighting design is first rate as well.

Ultimately, a Charles Busch play sinks or swims depending on its leading “lady,” and in Sands’ divine hands, Shanghai Moon is swimmingly good fun from beginning to end.

Luna Playhouse, 3706 San Fernando Road, Glendale.

www.lunaplayhouse.com

–Steven Stanley

November 15, 2008

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY