•A middle-aged immigrant biology teacher relives the genocide in his native Cambodia in which 2,000,000 of his countrymen lost their lives…

•A 40ish biologist obsesses over the impending extinction of a rare species of Bolivian beetle…

•A 15-year-old viola prodigy must come to grips with his mother’s terminal illness…

These are the threads which EM Lewis weaves together in her exquisitely poetic and deeply moving new play Song Of Extinction.

Though the Moving Arts world premiere production falls short in its supporting performances, the unforgettable work of its two leads and the visually stunning direction of Heidi Helen Davis make Lewis’ follow-up to her previous Infinite Black Suitcase and Heads a winner.

“There are things I know about extinction I don’t know how to tell to my students. Maybe I’m afraid to tell,” reveals Khim Phan (Darrell Kunitomi) in the play’s opening monolog. “Extinction is a very messy business,” he goes on. “In books it looks clean. But I remember extinction and it was not clean.”

Khim is a man who comes from a land of green fields “that smelled like grass under a wide blue sky and butterflies with yellow wings, glimmering in the sunlight.” It is also a land where the unthinkable happened, the near extinction of an entire nation of human beings.

Khim’s student Max Forrestal (Will Faught) lives in a house where the only food left in the refrigerator is a large, dusty jar of sauerkraut and a father to whom Max’s parting words upon leaving for school are “I hate everything about you.”

Max has reason to be angry. His father Ellery (Michael Shutt) seems more interested in keeping a unique species of Bolivian beetle from being killed off by the deforestation planned by megacorporation CEO Gill Morris (Trey Nichols) than in his wife Lily (Lori Yeghiayan), lying alone in her hospital bed only days from death of terminal cancer. (Tending her is a young resident (Tristan Wright) with about as much beside manner as a newly hired Walmart cashier.)

Khim is becoming concerned about this obviously intelligent student who cuts classes and has spent the past hour of biology “listening to something that was not biology” on his headphones. When Max asserts that “I’m not stupid,” Khim replies with humor and understanding, “I know. If you were this bad last year, you would be in Mrs. Rosenbaum’s class for retards.”

As Song Of Extinction progresses, not surprisingly a bond develops between teacher and student, especially after Max arrives in Khim’s office late on the night of the Sadie Hawkins’ Dance to ask for help with his biology project, a 20-page assigned report on the subject of extinction. Khim senses immediately that Max has much more on his mind than the project, and when he learns what Max has only today overheard, that his mother’s illness is terminal, Khim’s memories of the deaths of his own parents and 12-year-old sister return to the surface.

Lewis puts simple but very real and often powerful words in Khim’s mouth in the monologs he delivers to the audience. He talks about the 30,000 species gone every year. “That is why I assign a paper,” he explains. I believe this is worthy of some thought. But they look at me like small animals. Deers. Pigeons. Wolves.” And later, “If you teach high school, you must understand you will be teaching to purposefully blank faces for your whole life, and when they are not blank they will be angry.” As memories resurface, Khim says, “In this chapter on extinction, my country and history and family come up bitterly in my throat. And maybe I teach them about Cambodia without saying its name.” Lewis creates characters who defy easy categorization. Morris, for example, is not a right wing monster, but a man who is concerned with the 250 Bolivians the deforestation is providing with decent paying jobs, with the cleared land that can be used to grow soybeans on, and with the project’s 7.9 million dollar infusion of funds into the Bolivian economy.

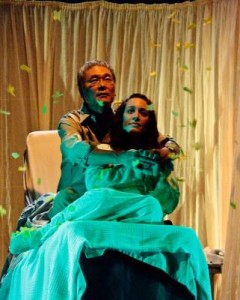

As Khim, Kunitomi performs with simplicity and eloquence, not attempting a Cambodian accent, but simply adding a hint of foreignness to his own voice. Kunitomi’s superbly understated work here is matched by the visceral power of the gifted young Faught. The 20-year-old Idahoan is totally convincing as a wounded teen struggling with the imminent loss of his mother and a distant father who seems already long gone. Moments between the middle aged teacher with life lessons to impart and the lost and lonely teen are electric in their intensity, and the scene in which Khim describes the paper which Max does indeed complete in time will move any but the most stony-hearted.

I wish that the other performances had the spontaneity and truth of the two leads. Hospital scenes lose power with a Lily who, despite death pallor makeup, seems hale and heart of voice and hardly days away from death. Shutt’s final scene with Faught, however, is one of the play’s most beautifully acted and powerful in its simplicity.

Director Davis, working with scenic designer Stephanie Kerley Schwartz and lighting designer Ian P Garrett, has given Lewis’s words even greater strength than they already have on the written page. Behind glass on either side of the stage are cabinets containing relics of Cambodia and Bolivia, snapshots, masks, and skulls, which light up at appropriate moments, and atop the proscenium are projected images of the two countries whenever they come up in conversation or in memory. Especially striking are scenes in which Lily’s hospital bed becomes a boat traveling down Bolivian waters in Lily’s morphine-induced dreams. Equally stunning are the shadowy white figures of Khim’s family (the wordless trio of Aileen Cho, Sophea Pel, and Vance Lanoy) which appear behind translucent glass windows whenever Khim’s memories take him back to the killing fields of Cambodia—“Our dead were scattered across those fields. Their besach—spirits—follow us wherever we go, asking if we will feed them, asking if we will burn their bones so they may rest. But there is no rest.”

Geoffrey Pope has composed Max’s Song Of Extinction (and other original music) as background to Lewis’s play. Jason Duplissea’s superb sound design combines music (including a haunting Cambodian cover of Joni Mitchell’s Both Sides Now) and sounds of the jungle, a hospital room, and pouring rain. High marks too for Laura Buckles’ costumes.

Following EM Lewis’s award-winning Infinite Black Suitcase and Heads, Song Of Extinction confirms the playwright’s unique gifts. Her exquisite writing and the gut-wrenching work of Kunitomi and Faught make Moving Arts’ production of Song Of Extinction one that will haunt you long after the lights have fallen on a father and his son.

[Inside] the Ford, 2580 Cahuenga Blvd. East, Hollywood.

www.FordTheatres.org

–Steven Stanley

November 7, 2008

Photos: Jay Lawton

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY