Adapting Double Indemnity for a 99-seat theater could easily prove disastrous. Make the wrong directorial, acting, or design choices and the enterprise could easily turn into an unintentional sequel to Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, Steve Martin’s brilliant parody of film noir.

Fortunately, the gods of “film noirdom” have shined down on Kathrine Bates’ stage adaptation of the James M. Cain novella for Theatre 40. Directed with respect and ingenuity by Beverly Olevin, and featuring pitch-perfect performances and design elements, Double Indemnity is a winner all around.

The novella Bates has used as her source material is, of course, best known for its 1944 Billy Wilder film adaptation. This, you may recall, is the noir in which insurance adjuster Fred MacMurray and married lover Barbara Stanwyck plot to kill her wealthy older husband after first taking out an insurance policy on his life—one which pays double if said husband dies in a fall from a moving train.

Double Indemnity (the play) differs in numerous plot points from the film, sticking more closely to the original novella (though not slavishly so). Where it does resemble the movie, and others of its genre (think The Postman Always Rings Twice, Out Of The Past, and The Woman In The Window just to name a few) is in its adherence to the conventions of film noir in terms not just of plot but of style and design. For all three elements, Theatre 40’s production merits highest marks.

Double Indemnity wouldn’t be “noir” without a crime (murder, naturally) motivated by greed and lust. There’s an investigation, of course, in this case by Huff’s boss, Keyes, who suspects that Phyllis’ husband’s “death by train” is all too convenient. There are betrayals and double-crosses (a must in film noir), and everyone smokes. (Fear not. Fake, smokeless cigarettes are used as effective substitutes for the real thing.) Our “hero” is morally flawed and our “heroine” is a sultry femme fatale and both of them believe that “the end justifies the means.” The setting is a film noir urban favorite, our own Los Angeles, and the characters meet in bars and nightclubs, and on dark street corners. The time seems pretty much always to be night and our adulterous couple, we know, is basically doomed from the start.

Both director and cast have done their film noir homework well. They are thankfully all on the same page, and that page could have been written by any of the classic film noir directors (Jacques Tourneur, Tay Garnett, Fritz Lang, Robert Siodmak, or the incomparable Wilder) or the stars who made film noir their home (Robert Mitchum, Humphrey Bogart, Lizbeth Scott, Victor Mature, and of course Double Indemnity’s Stanwyck and Edward G. Robinson). Acting is low-key and dialog is rapid-fire.

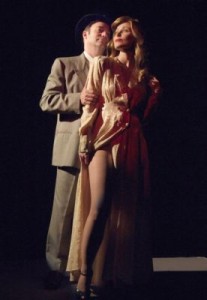

As Huff and Phyllis, Ed. F. Martin and Nancy Young underplay beautifully, as does Lary Ohlson as Huff’s friend, boss, and pursuer. Take their performances and insert them lock, stock, and barrel into any classic film noir and they would not be out of place in the slightest.

No one plays “everyman” better than Martin (one of the first roles I saw him in was as the title character in You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown), which makes him the perfect actor for Huff. (Recall that MacMurray of Double Indemnity the film went on to be the TV father of My Three Sons.) It is precisely because of Martin’s good-natured persona that (as was the case in the recent Kiss Of The Spider Woman) his “bad guys” are all the more interesting. Opposite Martin, Theatre 40 could not have made a better casting choice than that of Young. In her shoulder-length Rita Hayworth red hair and blood-red lipstick, the beautiful and talented actress is the perfect noir heroine/villainess, and the sexual chemistry between her and Martin is palpable. The affable Ohlson adds just the right hard edge to the role of Keyes to make him believable as both Huff’s friend and his formidable opponent.

Contributing in large measure to the success of Theatre 40’s Double Indemnity are its designers, who have captured the look and feel of film noir with authenticity and inventiveness. Christine Cover Ferro’s costumes are straight out of a mid-40s movie, from Martin and Ohlson’s wide, geometrically-patterned neckties to Young’s slinky silks and padded shoulders. Jeff G. Rack’s set design is deceptively simple, but wow is it clever! Modular units (all black to match the black floor and walls and designed with film noir appropriateness in oddly angled shapes) turn into desks, tables, car seats, a train platform, and even the bow of a boat (and are quickly rearranged in near darkness by trench coat and fedora-wearing actors doing double-duty as stagehands). Marc Olevin’s sound design features a must for film noir, voice-over narration by Miller as Huff, and appropriately noir music and sound effects.

Arguably the biggest design star of Double Indemnity is Jeremy Pivnick’s superb lighting, which features the stark light and dark contrasts which are a hallmark of film noir. (A look upward reveals an almost complete absence of colored gels.) Venetian blinds cast their distinctive shadows onto faces, furniture, and walls, and footlights recreate the upward shadows that are emblematic of film noir.

In supporting roles, the lovely Nicole McCloud (as Keyes’ young daughter Lola) looks like she stepped right out of an Andy Hardy movie with her permed long hair and angora sweaters, and she acts the role with sweetness and sincerity. In addition to moving the set pieces in their “strangers in the noir” outfits, Michael Shannon (as Phyllis’s ill-fated husband) and Benton Luke (as a potential eye-witness to just-before-the-crime) are effective in their supporting roles.

Bates’ script features a couple of delicious film noir tributes. In one sequence, Phyllis asks Huff what he thinks of her (very noiresque) turban which, she says, she was inspired to wear after seeing Lana Turner in The Postman Always Rings Twice. Later, Rita Hayworth’s name is mentioned in passing, and of course Hayworth was the quintessential noir temptress Gilda.

I approached Theatre 40’s Double Indemnity with a healthy dose of skepticism, but I was won over almost immediately and stayed transfixed from its striking opening scene (with a hospitalized Huff beginning his voice-over tale) to its final fadeout on our flawed, doomed hero. Film noir fans are hereby advised not to miss Double Indemnity.

Theatre 40, 241 S. Moreno Dr., Beverly Hills.

www.theatre40.org

–Steven Stanley

February 28, 2009

Photos: Ed Krieger

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY