The residents of Connemara, a small town in rural Galway, Ireland, appear not to need television or the movies for diversion. They’ve got each other—and their secrets and gossip and gleefully traded insults—to keep themselves and each other entertained night and day.

There’s 50something Mick Dowd, whose job it is to dig up the bones of the dearly departed in the Connemara cemetery in order to make room for new departures. (Seven years would seem to be the maximum time anyone gets to stay safe and cold in his or her grave in this Irish town.) A frequent visitor to Mick’s cottage is seventyish Maryjohnny Rafferty, who guzzles down poteen (that Irish beverage with among the highest amounts of alcohol in the world) as if it were mother’s milk, and wins (and cheats) at bingo with the best of them.

Memories go far back in Connemara. Maryjohnny still hasn’t forgiven the 5-year-olds who called her a “fat old biddy” even though the bunch of them have reached the ripe old age of 32, and no one has forgotten Mick’s wife’s death seven years ago, the apparent victim of Mick’s “drink drivin’,” though some have wondered if Mick himself might have given her a blow to the noggin before smashing his car into a tree.

Since it’s now time to begin disinterring bodies on the south side of the graveyard, and since Mick’s Oona has now been dead the requisite seven years, the next body to be dug up is none other than you know who’s.

Helping Mick with the digging is Maryjohnny’s grandson, young Mairtin Hanlon, a personable lad but a few watts short of a light bulb, a few bristles short of a broom, a few sheep short of a flock. You get the picture. Mairtin is just gullible enough to believe Mick when told that it’s “illegal in the Catholic faith to bury a body the willy still attached,” and that “they snip them off in the coffin and sell them to tinkers as dog food.”

Slightly sharper than Mairtin is his older brother, police officer Thomas Hanlon, who views every suspicious death with a healthy degree of doubt, whether Oona Dowd’s or the supposed heart attack of “the fattest bastard you’ve ever seen in your life” who was found naked (and dead) in his armchair with “only a pot of jam and a lettuce” in his six-foot-high fridge. The summer heat “might explain the stark naked,” explains Thomas, but not “the complete absence of food in his six-food fridge.”

Will the truth about Oona’s death finally be revealed? Will Maryjohnny learn whether Mick seals the disinterred bones in a bag and gently “eases” them in the lake (as he claims) or hammers them to nothing before throwing them “in the slurry?” Will a mallet be used to hammer anything other than the bones of the dead, say for example a human head still attached to a body?

These are but a few of the questions which may (or may not) be answered in A Skull In Connemara, Martin McDonagh’s “bone crushing dark feckin comedy,” the latest blue-ribbon production of North Hollywood’s Theatre Tribe, one of our most consistently superb local companies.

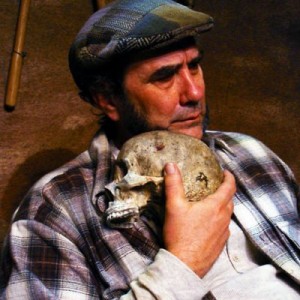

Ovation-winner Stuart Rogers directs a couldn’t-be-better cast of four—Morlan Higgens as Mick, Jayne Taini as Maryjohnny, Jeff Kerr McGivney as Mairtin, and John K. Linton as Thomas—on one of the most ingeniously designed sets you’ll ever see on the stage of an intimate theater. (More on Jeff McLaughlin’s brilliant design later.)

The ensemble of four have their Irish accents down pat, and what with McDonagh’s colloquial Galway dialog, a good deal of guessing is required about what words like “skitter” and “yobbos” and “eejit” mean (though context would indicate they’re not to be used in polite company). But people are people wherever they’re from, and these four are a deliciously quirky bunch and plenty of fun to spend a couple of hours with.

The foursome of actors never “go for the joke,” delivering McDonagh’s dry, wry lines with a matter-of-factness that allows the humor to creep up on you. Higgins’ gruff Mick, McGivney’s dim but eager Mairtin, and Linton’s humorously inept Thomas are all first-rate, as is the wonderful Taini, fresh from her stellar work in Lost In Yonkers. Taini so disappears into Maryjohnny’s Irish skin that she is unrecognizable as the same actress who brought Neil Simon’s German grandma to vivid life. That’s what’s called great acting. (Taini has taken over the role from Jenny O’Hara, pictured above.)

McDonagh’s script calls for a major scene change in the middle of the first act, from the interior of a run down cottage to a graveyard at night. The New York production apparently had a set which had the cemetery upside-down on the ceiling of the cottage, ready to rotate 180 degrees at the end of the first scene. McLaughlin’s first scene cottage offers no obvious clues as to how it will achieve the same transformation (though hinges on the upstage wall do give some hint to the observant). The change, when it occurs, is breathtaking. The set alone is almost reason enough to see the production.

Luke Moyer’s lighting is his usual fine work, with special snaps for the moonlight-through-haze effects during the graveyard scene. Thomas Burr’s costumes are suitably bedraggled. Thadeus Frazier-Reed’s sound design sets just the right Irish mood.

With this production as with those which have preceded it, Theatre Tribe exemplifies all that is great in Los Angeles theater—a cast of world-class actors, a gifted director, and a design team working miracles in a limited space (and on a budget). No wonder its run has been extended through the end of March. This is L.A. theater at its best.

Theatre Tribe, 5267 Lankershim Blvd., North Hollywood.

www.theatretribe.com

–Steven Stanley

March 12, 2009

Photos: Sara Shapley

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY