A play about stamps. How boring, you might imagine.

Wrong!

Though four of the five characters in Theresa Rebeck’s Mauritius do indeed know a good deal about philately, and though its plot does revolve around a pair of 170-year-old stamps, Rebeck’s darkly comic thriller turns out to be a never-a-dull-moment rollercoaster thrill ride featuring scheming con artists, feuding siblings, surprise twists, turns, and double-crosses, the F-word galore, hints of dark family secrets, and a black eye or two.

Following its 2007 Broadway run, Mauritius gets its West Coast Premiere at the Pasadena Playhouse in a couldn’t-be-better production. New York’s was directed by Tony-winning Doug Wright, but L.A.’s got Jessica Kubzansky, and a more gifted director you won’t find. In Kubzansky’s inspired hands, Mauritius has it all, drama, laughs, suspense, and a quintet of richly nuanced performances.

Following her estranged mother’s death, older half-sister Mary (Monette Magrath) has come back “home” for the funeral. Younger half-sis Jackie (Kirsten Kollender) can’t understand why Mary waited until Mom was dead to make her return, but Mary clearly had her reasons for leaving at age 16 and only now coming back, a dozen or so years later. Jackie’s been left with what seems like a mountain of debts—and a stamp album which might just hold the key to her financial solvency.

In order to find out just how much her mother’s stamp collection could be worth, Jackie asks a comic book store clerk for advice. He suggests she speak to a philatelist named Philip (John Billingsley) at his shop. The bored stamp expert refuses even to look at Jackie’s album, asking her, “Does this look like the ‘Antique Roadshow?’”—though he might be willing to examine her stamps for a $2000 minimum payment, or 2% of the net worth. Fortunately for Jackie, there’s a third person in Philip’s shop, sexy Russell Crowe look-alike Dennis (Chris L. McKenna), who offers to check out the stamps for free. Though Philip insists that Dennis “knows next to nothing,” the latter does know enough to recognize a pair of “Mauritius Post Offices” when he sees them.

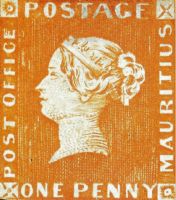

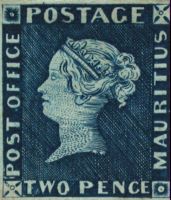

What, you may ask, are “Mauritius Post Offices,” and why are they so valuable? In a nutshell, the engraver of the pair of 1839 stamps (a “one-penny” and a “two-penny”) goofed, and instead of printing “Post Paid” on the edge of the stamps, printed “Post Office.” Since few of these “Mauritius Post Offices” remain in existence, a pristine pair (which Jackie’s seem to be) would go for millions and millions and millions of dollars.

There’s only one hitch for Jackie. Correction: There are plenty of hitches. First of all, Mary insists that the stamps are hers, as they belonged to her grandfather and not Jackie’s, and represent one of the few happy memories of Mary’s apparently traumatic childhood and adolescence. Then there’s Dennis, who arrives at Jackie and Mary’s mother’s home wanting to make a deal—but with which sister would that be? There’s also Philip, who bears a grudge against Sterling and would do anything to see that the stamps don’t end up in the hands of his nemesis.

Playwright Rebeck constructs Mauritius as a series of scenes of steadily escalating tension. Jackie inquires about the possible worth of the stamps. Dennis informs Sterling of their existence. Mary tells Jackie, “The album doesn’t belong to you.” Dennis and Sterling try to get Philip’s expert help in confirming the stamps’ authenticity before making Jackie an offer—before she finds out how much the stamps are really worth. Mary and Jackie spar over possession of the stamps. One of them punches. The other gets punched. Intermission.

And then, unfolding in real time (and with real tension), comes Act 2, none of which will be revealed here but wow the act is a doozy!

Rebeck’s play has been compared to Mamet (perhaps because people say “fuck” a lot and there are con-men involved) but the playwright has a voice of her own, one which combines her experience writing for crime shows like Law And Order and NYPD Blue, and her women’s relationship plays such as Loose Knit. At times, Mauritius reminded me of a 1960s “caper” movie, and it would make a great darkly comic suspense film, I think. What makes Mauritius more than just a crackerjack thriller, though, are the characters Rebeck has created and the performances by the Pasadena Playhouse’s stellar cast.

Kollender and Magrath look like they could be real-life sisters, but the resemblance between Jackie and Mary stops there. Whereas Jackie is street-tough and rough-tongued, the ladylike Mary seems incapable of foul language or of losing control. Jackie accuses her of acting, but if Mary is indeed playing a part, it seems to be one she’s created for herself in the years since leaving home. Rebeck gives few clues as to what happened to provoke Mary’s departure—that’s for the two actresses to create for themselves as “back-stories”—but it must have been traumatic enough that Mary waited until after her mother’s death to return. Kollender makes Jackie a scrappy fighter whose bravado hides a deeply scarred and frightened young woman. It is a whirlwind of a performance. Magrath does fascinating work as a woman who’s worked hard to leave the “old Mary” behind. Is she a heartless, selfish bitch, or a damaged soul who truly believes that the stamp album is her one connection to the only happiness she knew in her childhood? What’s particularly interesting about Magrath’s performance is that she doesn’t give away the answer, or at least not until the very end of the play.

The men are equally sensational, beginning with some powerhouse work by Abruzzo. His Sterling is truly scary, a tough guy who can intimidate simply by standing in a room, but what elevates his performance (and Rebeck’s writing) are scenes which reveal totally unexpected sides to Sterling. In fact, in Mauritius, no one turns out to be the person we first think we have met.

I’d only seen McKenna (as Tony Kirby) in the Geffen’s 2005 revival of You Can’t Take It With You, but his performance here makes me hope to see much more of this edgy leading man on our stages. McKenna makes the role of Dennis, which scored Bobby Canavale a Tony nomination, entirely his own. Charming, dangerous, unpredictable, and romantic—his Dennis is all of the above, and a magnetic stage presence to boot.

Finally, in the smaller but plum role of Philip, Billingsley starts off schlumpy and sarcastic, then turns sly and devious. Like his costars, this is rich and thoroughly three-dimensional acting.

Mauritius is a play that could work well in a black box theater with minimal sets, but seeing it in a Pasadena Playhouse caliber production is icing on Rebeck’s tasty, tangy cake.

Tom Buderwitz is at his most dazzling in his revolving set design which transforms from a shoddy stamp shop to a shoddy café to a shoddy living room—and does so absolutely gorgeously. Jaymi Lee Smith’s lighting and Maggie Morgan’s costumes complement Buderwitz’s set and Rebeck’s story to perfection. Tim Weiske has choreographed some exciting, realistic fights. Still, it is John Zalewski’s original music and sound design that set the mood and heighten the suspense immeasurably. My guess is that most in the audience are only vaguely aware, if at all, of the very low hum that accompanies some of the most edge-of-your-seat moments, but everyone feels its effect. Subtle and brilliant.

It’s been a great two weeks for drama, first with The Manchurian Candidate, and then Stick Fly, and now Mauritius. I didn’t know quite what to expect from a play about sisters and stamps, but what I got was something very special indeed.

Pasadena Playhouse, 39 South El Molino Ave., Pasadena.

www.pasadenaplayhouse.org

–Steven Stanley

April 14, 2009

Photos: Ed Krieger

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY