Superbly directed by Robert Mammana and featuring a tour de force lead performance by M Butterfly’s Sam R. Ross, Breaking The Code is, simply put, must-see theater. Despite its 1930s to 1950s English setting, Hugh Whitemore’s biodrama remains vital and relevant to 21st Century America, both as a reminder of a time not so long ago when a confession of homosexual acts could send a man to prison, and as proof that “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

Breaking The Code is true story of Alan Turing, known as the father of modern computing, whose work in decrypting coded Nazi messages is said to have hastened the end of the World War II in Europe by two years. Yet rather than receiving recognition and renown for his achievements, Turing ended up dead at the age of 41, the victim of an apparent suicide.

Breaking The Code is true story of Alan Turing, known as the father of modern computing, whose work in decrypting coded Nazi messages is said to have hastened the end of the World War II in Europe by two years. Yet rather than receiving recognition and renown for his achievements, Turing ended up dead at the age of 41, the victim of an apparent suicide.

Whitemore’s gripping drama documents both Turing’s brilliant work as a scientist and his life as a homosexual at a time when the word “gay” meant only merry and carefree. Turing, who suffered from a painful stutter and a self-confessed lack of a social filter (“I’m always saying things I shouldn’t say”), brought about his own downfall by casually revealing to the police detective investigating a break-in and robbery at this home that he had been having a sexual relationship with one of the alleged perpetrators. Homosexuality was illegal in England until 1967, and regarded as a mental illness. Given a choice between imprisonment and probation, Turing accepted chemical castration via estrogen hormone injections. (The injections caused him to grow breasts.) Two years later, he was dead, apparently from a cyanide-laced apple left half-eaten beside his bed.

Breaking The Code moves back and forth through time, beginning with the winter afternoon when Turing went to the local police station to report the theft of “a shirt, five fish knives, a pair of tweed trousers, three pairs of shoes, a compass, an electric shaver, and a half empty bottle of sherry. Not much of a haul.” Turing’s contradictory testimony about “George,” a man who Turing suggested might have committed the crime, leads detective Mick Ross (Armand DesHarnais) to suspect that Turing may not be telling the whole truth, or perhaps even not much of the truth at all.

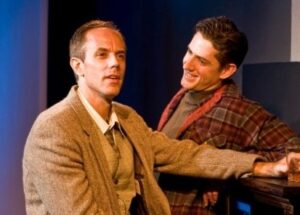

The story then flashes back to a weekend in the late 1920s, when teenage Alan brought schoolmate Christopher Morcom (David Robert May) for a visit to his family home. The scene also introduces us to Turing’s slightly dotty mother Sara (Sarah Lilly). Though we never see Chris again, and later learn of his death from tuberculosis at the age of nineteen, Chris’s (and May’s) presence haunt the rest of the play, as the lost (and never consummated) love of Turing’s life and the inspiration for his life’s work.

Back in the 50s, we meet hunky bisexual Ron Miller (Adam Burch), a young working class bloke picked up by Alan in a bar, who ended up the catalyst to Turing’s eventual arrest and conviction for “gross indecency.” Then flashing back to the war years, we observe Alan’s job interview with Dillwyn Knox (David Ross Paterson), to whom the scientist explains his concept for the Turing Machine, which Alan believed “could carry out any mental process whatsoever,” the forerunner of today’s computers. We also meet Pat Green (Joanna Strapp), a lovely and intelligent young woman who ends up falling in love with Alan despite the realization that he was the sort of man who might love her, but would never be able to make love to her.

Back in the 50s, we meet hunky bisexual Ron Miller (Adam Burch), a young working class bloke picked up by Alan in a bar, who ended up the catalyst to Turing’s eventual arrest and conviction for “gross indecency.” Then flashing back to the war years, we observe Alan’s job interview with Dillwyn Knox (David Ross Paterson), to whom the scientist explains his concept for the Turing Machine, which Alan believed “could carry out any mental process whatsoever,” the forerunner of today’s computers. We also meet Pat Green (Joanna Strapp), a lovely and intelligent young woman who ends up falling in love with Alan despite the realization that he was the sort of man who might love her, but would never be able to make love to her.

Whitemore sketches the portrait of a deeply complex central character, a man who regards World War II as “first and foremost … a most unfortunate interruption to my work.” The playwright shows us a man ahead of his time in his understanding of his sexual orientation and his unwillingness to play a socially acceptable role by marrying Pat, despite her offer to be his willing accomplice in a marriage of convenience. When Turing declares nonchalantly to detective Ross that he is “having an affair” with Ron, he reveals a guileless unawareness of the rules of the society in which he lives. (When Ross asks Alan if he realizes that he has committed a criminal offense, the clueless scientist replies, “Isn’t this rather beside the point?”)

Mammana’s directorial vision is evident from the production’s striking first scene, a stunning tableau of Ross standing in front of a blood red scrim, apple in hand, as the voice of Snow White’s evil queen (from the Disney animated feature) talks about the poison apple that was nearly Snow White’s downfall, the significance of which will become evident as the play progresses. A later scene has both Turing and detective Ross facing the audience, allowing us to see the face which each presented to the other during police interrogations. Mammana cleverly has Turing illustrate his explanation to Knox of “consistency, completeness, and decidability” with a trio of liquor bottles (though truth be told, the scientist’s explanation still went whoosh right over my head).

As Turing, Sam R. Ross tops his standout performance in M Butterfly, transforming himself into the complex British scientist from the top of his head to the tips of his toes, the man’s awkward body language and persistent stutter at times almost painful to watch. There is humor in Ross’s performance as well, as seen in his frustration with a mother who can’t seem to grasp the difference between iodine and iodates and who thinks that her grandfather’s cousin “invented” the electron. (“He didn’t invent it, Mother; electrons exist, you can’t invent them.”) Ross’s Turing positively bubbles with excitement when describing the Nazi Enigma machine’s 17,557 times 60 combinations. His is not only a great performance, but one requiring enormous stamina. Ross not only has several challenging monologs (each running several pages in the play’s written form), he also appears never to leave the stage throughout the play’s two-and-a-half hour running time.

As Turing, Sam R. Ross tops his standout performance in M Butterfly, transforming himself into the complex British scientist from the top of his head to the tips of his toes, the man’s awkward body language and persistent stutter at times almost painful to watch. There is humor in Ross’s performance as well, as seen in his frustration with a mother who can’t seem to grasp the difference between iodine and iodates and who thinks that her grandfather’s cousin “invented” the electron. (“He didn’t invent it, Mother; electrons exist, you can’t invent them.”) Ross’s Turing positively bubbles with excitement when describing the Nazi Enigma machine’s 17,557 times 60 combinations. His is not only a great performance, but one requiring enormous stamina. Ross not only has several challenging monologs (each running several pages in the play’s written form), he also appears never to leave the stage throughout the play’s two-and-a-half hour running time.

The supporting cast’s performances, in considerably smaller roles, are uniformly fine. Burch mixes macho swagger with hints of both danger and tenderness to create an indelible portrait of a man far ahead of his time in his nonchalant acceptance of his bisexuality. DesHarnais, with a pitch-perfect Manchester accent, makes detective Ross so much more than the villain of the piece, showing us a fully three-dimensional man who comes to feel sympathy for and even understanding of his “victim.” Following some slight stumbling over lines in her first scene, Lilly ultimately gives one of the play’s most powerful performances, particularly in a deeply moving scene in which Alan comes out to her, to unexpected results. A very sympathetic Strapp brings warmth and understanding to the role of a woman who loved Alan with full knowledge of the man he was. Barry Saltzman makes a strong impression in his brief scenes as John Smith, whose role in the play is to warn Turing of his potential security risks as a homosexual.

Paterson is simply marvelous as Knox, like leading man Ross acting with his entire body, particularly in Act 2 when his character returns, considerably debilitated by age and the war, to warn Alan that discretion is now of the essence, and to suggest that “understanding and companionship” are more important in a relationship than passion,” words which fall on the deaf ears of a man who believes that “perhaps one brief moment of passion is worth more than twenty years of uneventful companionship.”

Passion was something Turing was unwilling to forego, as illustrated by a pair of memorable cameo performances which bookend Breaking The Code. Angelic May’s sweet and honest work as Chris, the great love of Alan’s life, continues to resonate long after his one brief scene ends. Alan’s inability ever to find someone to take Chris’ place in his heart makes Michael Tauzin’s performance as “Nikos from Ipsos,” a Greek boy who becomes Turing’s lover during a brief vacation in Greece, all the more powerful. Speaking not a word of English, the brilliant young actor not only convinces us that he is a native Greek speaker who understands none of what Alan is saying to him, but also that his affection for and attraction to the older Brit are sincere and heartfelt.

Set/lighting designer August Viverito positions a back-lit scrim as the upstage wall of his set, which takes on different colors according the scene being played, from the blood apple red of the opening and closing sequences, to green when he describes to Ron a nightmare he’s had over and over again since childhood. The multitalented Viverito also designed the fine array of period costumes and John McMinn’s sound design deserves high marks as well. Alisa Banks assisted Mammana in directing Breaking The Code.

If Alan Turing were alive today, the 96-year-old would probably express satisfaction at the progress made by gays and lesbians in Britain, the United States and Europe. Gay marriage was so beyond unimaginable during Turing’s lifetime that its becoming reality would seem nothing short of miraculous. (Attending a performance of Breaking The Code should be required of LGBTs under a certain age who have no concept of what gay life was like only a half century ago.) At the same time, there are still many countries in which gays and lesbians are treated far worse than even Turing was, and only recently, linguist Dan Choi was booted from the U.S. military despite the vital need of his abilities as an Arabic speaker to the war effort in the Middle East. The more things change, the more things indeed stay the same.

Breaking The Code is a testament to how far we’ve come, and how far we still need to go. It is not to be missed.

The Production Company, Chandler Studio Theatre, 12443 Chandler Blvd., North Hollywood.

www.theprodco.com

–Steven Stanley

May 15, 2009

Photos: Robert Douglas

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY