The dark is a scary place to be. Just think back on all the movie and TV thrillers with the word “dark” in their title: Dark Shadows, The Dark House, Whispers In The Dark, Are You Afraid Of The Dark, Dark Water, and of course Elvira Mistress Of The Dark—to name just a few.

What if that darkness were perpetual, inescapable? That would certainly up the fear factor, right?

This is the premise of Frederick Knight’s stage and screen thriller, Wait Until Dark, the tale of a recently-blinded woman terrorized by a killer in her New York City basement apartment—who evens the odds by placing not only herself but also the killer (and the audience) in pitch blackness.

Lee Remick originated the role of Susy Hendrix on Broadway in 1966, though it is probably Audrey Hepburn’s 1967 big screen Susy that most people remember when they hear the words Wait Until Dark. There are doubtless few movie or theater buffs who have not seen either the movie or one of the countless regional or community theater productions staged every year.

I’ve seen Wait Until Dark performed by college students, in community theater, and in Equity Waiver productions, but only this past weekend did I have the chance to finally experience this classic thriller in a big stage professional production and get a bit of a taste of what Broadway audiences might have experienced four-plus decades ago.

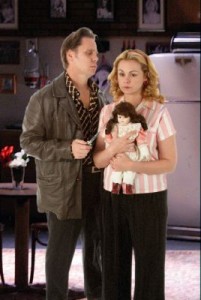

Professional criminal Harry Roat (Don Harvey) has reason to believe that a heroin-filled doll is hidden in the apartment of photographer Sam Hendrix (Brian Crawford Scott) and his wife Susy (Libby West). It seems that Sam brought the doll across the Canadian-U.S. border as a favor to a woman he happened to meet at the airport—and in order to get his hands on it, Roat enlists the help of a pair of thugs, Mike Talman (Louis Lotorto) and Carlino (John Richard Petersen).

Roat’s plan is a complicated one, involving Mike’s posing as an old friend of Sam’s, Carlino’s impersonating a New York police detective, and Roat’s assuming a number of disguises. All of this is contingent on Susy’s being home alone, and the crooks’ being able to take advantage of her blindness—which they see as a weakness. In a clever plot twist which has helped make Wait Until Dark an audience favorite, Susy turns this liability into an asset in the play’s chilling climactic scene.

West creates a fascinating portrait of a woman still learning to live with blindness. Leaving her cane at the door when entering her apartment, Susy has mastered how to maneuver from chair to table to kitchen to desk by counting steps, always walking in straight lines and making ninety degree turns. A chair which the thugs have moved, and which she bumps into, is Susy’s first clue that something is wrong. Later, her heightened sense of hearing alerts her even further that something is amiss. Why is Carlino dusting her apartment when it’s kept spic-and-span, and why do her visitors keep opening and shutting the blinds when the apartment is perfectly well lit?

Pivotal to the plot is a nine-year-old neighbor girl named Gloria (Brighid Fleming), who starts out as a thorn in Susy’s side and ends up her greatest asset in gaining the upper hand against Roat and his cohorts.

Knott’s plot takes so many twists and turns that even after seeing the play five times, I mostly just relax without trying too hard to follow its complexities, enjoy the ride, and wait until that last scene which never fails to provoke shrieks.

Like another recently reviewed 1960s classic, Wait Until Dark can exist only in a pre-cell phone era. Not only can Susy not contact Sam wherever he might be, a phone booth (remember them?) visible from their apartment proves essential to the unraveling of the plot. If Susy and her visitors had cell phones, there’d be no Wait Until Dark. And if the play were a contemporary one, no one in her right mind would tell a nine-year-old girl to hop in a taxi to the Port Authority Bus Terminal and meet every bus coming in from Asbury Park. The world has indeed changed since 1966.

The Norris has as always assembled a top-notch cast to bring Knott’s tale to suspenseful life. West is a regional theater treasure and, as always, a powerful stage presence here. Her Susy is a woman who exhibits the same guts and pluck in her attack against the diabolical Roat as she did when responding to the loss of her sight. Hers is not to reason why but simply to do (and hopefully not die). Acting without the benefit of the mirror to her soul, West nonetheless lets us see Susy’s intelligence at work, and when the brave facade begins to evaporate as danger approaches, the effect is all the more powerful for having been there previously.

Lotorto’s slightly off-center stage persona gives an extra edge to Mike Talman, and plants that smidgen of doubt in Susy’s head, even while she welcomes the help of this apparent ally. Petersen adds a nice comic touch to Detective Carlino, Scott is appropriately stalwart and sympathetic as Sam, and young Fleming is an absolute delight as Gloria—and the antithesis of the stereotypical “child actor.” Allan Lynch and James Sluyter appear briefly but to good effect as a pair of police officers. Finally, in the pivotal role(s) of Harry Roat, Harvey gives a strong performance which will be even stronger if he ups the CSF (creepy, scary factor) a notch or two.

With Wait Until Dark, director Aaron proves himself as adept at suspense as he is at musicals (Great Expectations, Cabaret) and comedies (The Graduate, Lend Me A Tenor). His design team aids immensely. James W. Gruessing, Jr. has created a beautifully laid-out and decorated basement apartment set. J. Kent Inasy’s lighting is crucial throughout the play, and he has done a masterful job here—as always. Shon LeBlanc’s costumes are first rate, and if you wonder why Susy’s culottes seem a bit baggy and even frumpy, there’s a reason for that—see if you can figure it out. Best of all, is Max Kinberg’s finely-detailed sound design (the refrigerator even whirrs when its door is opened) and very effective original “suspense movie” soundtrack. (Only one slightly “off” music cue foreshadowed and thus dampened the effectiveness of the play’s climactic shock moment.)

There’s something to be said for the intimacy of a small theater production of Wait Until Dark where the audience finds itself virtually in Susy’s apartment, and feeling especially claustrophobic when the lights go out. But there’s also something special about seeing Wait Until Dark a la the Broadway original, in a big stage, bigger budget production like this one.

Ultimately, though, it’s the writing, direction, and performances that make for a first-class Wait Until Dark, and all three are front and center stage at the Norris.

Norris Theatre For The Performing Arts, 27570 Crossfield Drive, Rolling Hills Estates.

www.norriscenter.com

–Steven Stanley

May 2, 2009

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY