If ever a production could be called unique, then Tom Stanczyk’s Block Nine is just that production. Press materials describe it as “an unapologetically same-sex, retro-noir 1930s gangster homage” and “an exploration of sexuality, gender, stereotype, romance and aggression (in) an underworld full of guns, jail breaks, booze and bodies.” How’sthat for something out of the ordinary?

Though Block Nine was written specifically for an all-male cast, the always cutting edge Elephant Theatre Company elected to produce an all-female version as well, the dueling duo staged by different directors and running simultaneously in rep—with apparently quite different results.

The “Fellas” version reviewed here features a sensational cast of L.A. talents, all of whom have done their film noir homework. The resulting production ends up somewhere between homage and spoof, though it is played dead serious, the better to feature both laughs and thrills.

Hank (Jeremy Glazer, who alternates with Dominic Rains in the role) is a hard-boiled hunk of a cop about to go undercover in the criminal underworld of bleach-blond sociopathic gangster Cody (Max Williams) and his trio of minions Nails (Darryl Armbruster), Putty (Ryan Radis) and Johnny Bell (Josh Breeding). “I’m sorry my dreams wake you,” apologizes a distraught but ever handsome Hank to Phil (Kenny Suarez), his fellow cop (and lover) on the night before his undercover assignment in the big house is to begin. Who wouldn’t be a bit freaked out about having to spend time behind bars in the guise of hardened criminal “Lockjaw”?

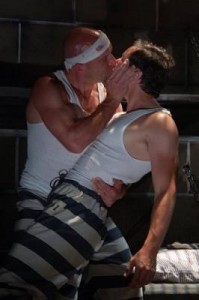

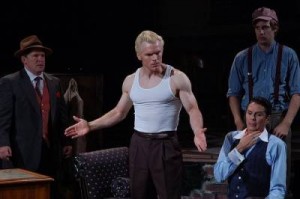

Meanwhile raspy-voiced Cody, his bulging muscles barely contained within a skin-tight wifebeater, is at home with his elegantly-dressed French-accented lover Armand (Louis Douglas Jacobs), who is doing his darnedest to convince the “big galoot” to join him on a weekend getaway to God’s Country, also known as Longwalk. “I love you,” Armand confesses. “There, I’ve said it. Finally. Does that scare you? Now come here and kiss me, you big lug.” Apparently, a declaration of love is the last thing Cody wants to hear. “Je m’appelle sick of you,” he tells Armand before slapping him, then kissing him, then slapping him again, and then kissing him long and hard. (Block Nine may set a record for the number of long, hard same-sex kisses and slaps.)

Before long, Hank aka Lockjaw is in a jail cell trying to get vital information about Cody from cellmate Lips (Matt Rimmer), whose moniker apparently comes from his expertise as a kisser, as Hank will soon discover. Meanwhile, Armand lies dead in Cody’s living room, the gunshot victim of his highly dangerous and quite possibly deranged lover.

It’s about this time that I stopped trying to follow Block Nine’s convoluted plot and simply sat back and let the noir surround me.

As the above quotes indicate, Stanczyk is a master at recreating 1930s movie slang, and his cast utters his spot-on dialog with utmost seriousness. In fact, under Pete Uribe’s dynamic direction, the entire Block Nine ensemble give memorable performances in the iconic tradition of 30s/40s Hollywood leading men and character greats. Glazer effective channels Alan Ladd, Richard Widmark, and Burt Lancaster as the story’s tough, handsome, intrepid hero. There’s a bit of James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson combined with the platinum blond locks of Blade Runner’s Rutger Hauer and the body of Schwarzenegger circa Terminator 1 in Williams’ hyper intense Cody. Rimmer recalls every behind-bars tough guy ever to inhabit a Hollywood prison cell, and Suarez makes for a stalwart, supportive lover to Glazer’s Hank, the kind of role Jeanne Crain might have played circa 1945. Getting the most laughs are Cody’s Three Stooges-like henchmen, compact tough guy Armbruster, squeaky-voiced Radis, and lanky blond Breeding. Possibly best of all is the wonderful Jacobs, Hedy Lamarr in male drag.

Stanczyk’s script could stand more than a bit of trimming, especially in the second act. Excellent as Williams is, a little Cody goes a long way, and Act Two features two very long sequences featuring the increasingly unstable blond gangster.

Perhaps the biggest stars of Block Nine are its designers. Danny Cistone’s set recalls the nightmarish angles of The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari, and Joel Daavid’s lighting sends sunlight through venetian blinds to cast narrow horizontal shadows on faces, and from stage level pointing up to cast crisp dark film noir shadows on walls. Jack Arky’s sound design and original music add to the mood and suspense, and Jacobs’ costumes pay memorable tribute to the noir et blanc fashions of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

If only my schedule would permit a couple more visits to Block Nine, I’d enjoy trying to unravel a bit more of the twisted plot threads, and then seeing how the Dames tell the same story as the Fellas. Block Nine is a must-see for fans of gangster flicks who don’t mind a bit of boy-on-boy (or girl-on-girl) kissing (and slapping) amidst shadows and gunshots galore.

Lillian Theatre, 1076 Lillian Way, Hollywood.

www.plays411.com/blocknine

–Steven Stanley

August 30, 2009

Photos: Joel Daavid

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY