At some time in the perhaps not so distant future, after a series of “ecological events” has altered civilization as we know it, a trio of teenage boys have set up house in a primitive one-room mountain cabin somewhere in the Pacific Northwest. Despite the cataclysms that have befallen society, the “family unit” has somehow found a way to survive in Henry Murray’s Treefall, now in its world premiere engagement by Rogue Machine. Though a post-apocalyptic nightmare fairy tale would not be my usual theatrical cup of tea, the performances of its talented, charismatic young cast, the contributions of a superb design team, and some ultimately moving, thought-provoking writing make Treefall an absorbing piece of theater.

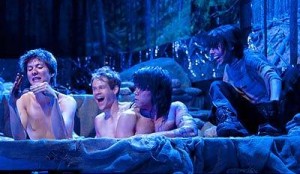

Flynn (Brian Norris), August (West Liang), and Craig (Brian Pugach) attempt on a daily basis to recreate the kind of family each finds it increasingly difficult to remember. Flynn, as Dad, reads the newspaper, probably one from years ago. August, as Mom, sets the table while wearing a scraggly wig and worn-out dress. “Son” Craig, meanwhile, carries on a conversation with a doll about one-time everyday things like homework and knock-knock jokes, and offers to do the dishes “if I can wear the Mommy wig.” (It seems that whoever wears the wig gets to assume the maternal role.) Before sitting down to eat, the boys offer a ritual “blessing” by recalling things they fear forgetting. One remembers fresh milk (“It was cold and thick and white like liquid eyeballs.”) For the others, it’s chocolate cake and peanut butter whose memories they bring up, and pretend to be eating as they dine on stewed tomatoes.

The threesome find themselves beginning to go stir-crazy, though, trapped indoors during daytime hours by a sun whose rays could now prove fatal. (Flynn has a nasty looking sunburn on one of his shoulders.) As they converse, we learn a few significant facts about their pasts. The mother of one had had traveled hundreds of miles to bring her son to safety before her death to “the virus,” her husband already having died during “the second migration.” Another’s mother had simply gone out when he was ten and never come back. Craig was brought to Flynn and August from “beyond the ash line.” The three boys pray on a daily basis to “the Mommy Altar,” a makeshift tabletop shrine on which sits the aforementioned wig, a necklace, and other maternal memorabilia. The familial roles Flynn and August have assumed have begun to extend to the bedroom, and August is none too happy about the way Flynn has started using him “like a girl.”

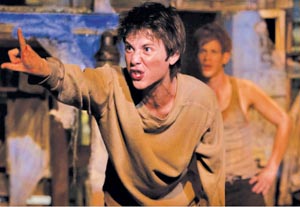

One day after sunset, Flynn and August return from foraging—with a fourth teenager in tow, a somewhat surly, raspy-voice boy named Bug (Tania Verafield). Despite Flynn’s reservations, the two boys have agreed to let Bug stay with them for a few days. Not long after, a shocking discovery is made. Bug is a girl, and her presence among them will set off a series of life-changing, and in some cases catastrophic turns of event.

Under John Perrin Flynn’s excellent direction, four talented young actors give unique, magnetic performances in a production that grows steadily more powerful, especially in its dramatic second act.

Liang is striking, as always, as August, the family member most frustrated by the role he’s being forced to assume, and consumed with a desire to escape, especially once the delicate balance of their three-way relationship is upset by Bug’s arrival. Norris does equally memorable work as Flynn, torn between his devotion to Craig, his desire to somehow remain part of a family, and the uncontrollable needs of his testosterone-filled adolescent body. Verafield excels in what is virtually two performances, first as the scrappy boy Bug initially appears to be, and then as the emotionally wounded young woman she is in reality. Finally, in the role of Craig, the gifted Pugach leaves an indelible impression as a boy dealing with the death of his real parents, the tensions between his surrogate mother and father, and a growing realization of his alternate sexuality. Scenes in which Craig, sometimes wearing the “mommy wig” and lipstick, carries on two-way conversations with his dolly, quoting Shakespearean verse which he may or may not understand, or devours a Superman comic book, declaring “I’d like to think that Superman escaped his dying world,” alternate between amusing and tragic.

Stephanie Kerley Schwartz has designed a striking, multi-locale set filled with the abandoned detritus of society as we know it, foil-surrounded photos of dead forests providing a grim backdrop. Costumes by Lauren Tyler appear decades old and worn. Though apparently a number of lighting cues were lost due to the addition of a new light board only an hour or so before the performance reviewed here, Leigh Allen’s lighting design managed to shine through, particularly in the play’s devastating final tableau. Best of all is Joseph “Sloe” Slawinski’s almost indescribable sound design, which mixes fragments of news reports, and what appear to be sounds of war, fire, static—a virtually unrecognizable cacophony, most particularly the terrifying noise made by falling trees, each of which might at any second obliterate the young people’s sanctuary. (It was only through a post-performance discussion with a cast member that I learned the latter piece of vital information. I had heard “trains,” and my guest nothing at all, so a way needs to be found of insuring that the audience hear the words “tree” and “fall.”)

In lesser hands, Treefall might have come off as pretentious or “fringe-y,” but director Flynn and his cast made me care about Murray’s characters and the production’s design team created a very real fantasy world for them to live in. I ended up quite engrossed—and moved—by Treefall.

Rogue Machine, Theatre Theater, 5041 Pico Blvd., Los Angeles.

www.roguemachinetheatre.com

–Steven Stanley

August 13, 2009

Photos: John Flynn

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY