Ryun Yu returns to East West Player this month for their season opener, Yazmina Reza’s Tony-winning Art. This follows his much lauded solo performance in Jeanne Sakata’s Dawn’s Light: The Journey Of Gordon Hirabayashi, for which Ryun was awarded Dramatic Performance Of The Year by StageSceneLA. Among Ryun’s many TV appearances are guest shots on Numb3rs, The Unit, ER, 24, Huff, Curb Your Enthusiasm, Cold Case, and The Shield as well as a recent recurring role on Beyond The Break. Ryun’s film credits include Only The Brave, Kissing Cousins, and The Brother’s Solomon. Ryun has appeared on stage in Lodestone Theatre Ensemble’s One Nation, Under God and The Golden Hour, in the West Coast Premiere of Take Me Out at the Geffen Playhouse, and and in other plays he discusses in this interview. Getting ready to open a three-actor play leaves a performer little time for anything but rehearsal, so we’re indeed grateful to Ryun for taking time from his busy schedule to answer our questions!

Ryun, you’ve already accumulated a number of “firsts” in your life. You were the first Korean American to train at the Royal Academy Of Dramatic Art In London. What prompted your decision to study there?

I was in love with the great Shakespearean actors. My heroes at that time were Kenneth Branagh, Ralph Fiennes and Anthony Hopkins, and they had all gone to school there. I wanted to be part of a great tradition, and I wanted to get a training that would allow the character to fully express himself through my body, voice, and behavior.

How did your experiences there change you?

It taught me so much about who I was. I didn’t fully realize that I was an Asian-American when I went there. I didn’t recognize that my ethnicity and my country were two gifts that were given to me, two things that would make me unique. I was quite willing to sacrifice who I was to become a great actor, but thank God it didn’t work. I had great training, I learned a tremendous amount about acting, but then I started to become aware of something inside me that was pulling me away from the life I had imagined for myself in the English theater.

Do you think that your being there affected your fellow drama students and your teachers?

I don’t really know. I know that they affected me tremendously. I had a fantastic principal, Nicholas Barter, who went out of his way to create opportunities for me. I had teachers who really went the extra mile. And my fellow students were so talented, it would constantly push me. I loved them, and I do miss them to this day.

You’re also the first student to have earned a theater degree at the Massachusetts Institute Of Technology. How did this come about?

I went to MIT because I loved it there. The people were so interesting, and the atmosphere was so electrically charged. I remember that at one of the other colleges I visited, one of the professors said “Any of these schools you got into are good. Go to any of them, except for MIT—the people there are weird.” I went to MIT and I found that I was one of the weird people. I think I am a mix of Star Wars and the old great theatrical actors, Edmund Kean and Eleanora Duse. I would be fascinated by the technology at MIT—we had the Internet before the world did and some things that the world doesn’t have yet, like holographic television—but then I would spend all day and night in the theaters there, putting on plays there, sometimes, late at night, just standing on the stage of an empty theater, loving the power of that spot where all the attention is focused, the potential electricity that a gifted performer could bring to this soaring place. I studied computer science, but I couldn’t take my mind off what I was obsessed with. I realized I had to officially spend my time on what I was actually spending my time on. I had a wonderful professor, Alan Brody. He and I created the major together.

How exciting! Did they have theater classes there?

They had great classes, but not yet a major. Kermit Dunkelberg, who had studied with Grotowski in Poland, was the head of our Shakespeare group. Kim Mancuso, who had graduated from Yale in playwriting, was one of our teachers. It was very vibrant and alive.

Have there been a bunch of other theater grads since you?

There were two in the year after me. I don’t know after that.

You also write in your bio, “his parents still talk to him.” Did you encounter any resistance from your parents when you told them that you wanted to pursue a career in acting?

Oh dear yes. They are Korean after all.

So how did they come about giving you their blessing?

I had thought—“I don’t need their support”. And then I was doing Hamlet at MIT, and my dad came out to see it. After the show, he came backstage and said “We will support you.” I was so moved. Now I can imagine the sleepless nights and trouble this had caused my parents—and the extraordinary generosity and love they had towards me to come to that point of view.

That’s really wonderful. I’ve taught hundreds and hundreds of Koreans in my day job, and I know what a big step that must have been for them.

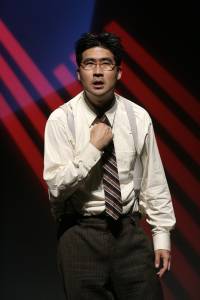

Ryun in What I Heard About Iraq (photo: Ed Krieger)

and in Dawn’s Light: The Journey of Gordon Hirabyashi (photo: Michael Lamont)

You’ve been in a couple of “political” plays—What I Heard About Iraq, at the Fountain, dealing with the Iraq war, and Dawn’s Light: The Journey Of Gordon Hirabayashi, about the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Did their political nature have anything to do with your accepting these roles?

I generally look for something that will be artistically interesting, and that does often mean that plays have some relevance politically.

Can you talk a bit about how audiences reacted to these two plays in Q&A’s or simply in conversations with you?

The Iraq play caused some heat. Some people walked out. People were yelling at each other sometimes, telling each other to shut up. We had former soldiers who agreed with the point of view of the play, others who disagreed. I have to say there was something very bold about this, about being a Republican and walking into this atmosphere and having the courage to speak up. It was amazing to me that all this could come about from a play which was composed entirely of quotes and statistics, though of course edited to form a very strong point of view. The Hirabayashi play was less controversial, though the ability of the simple power of his life to capture people’s interest and imagination was really something.

Dawn’s Light was about the journey of one heroic young Japanese American, but I imagine it was a journey for you as well, working together with playwright Jeanne Sakata and director Jessica Kubzansky. What did you learn from the experience?

Gordon Hirabayashi taught me so much of what it is to be a man. I did a lot of research on the time, on the places where he grew up and lived. As the work went on, I became a little awed. I think like many extraordinary people, it might be easy for him to hide those world-conquering qualities that he possesses. Everything that he did, he did from the perspective of a Nisei, a second-generation Japanese-American. And that meant that when he did something, he generally did it with a kind of restraint and understatement. And what he did … I think it took me quite a while to comprehend what he did, much less how he did it. 22 years old, the United States Government, your whole community, and your own family against you, and you stand up for a principle? For a right expressed in the Constitution? The love he must’ve had for the Constitution, for what American stood for in its highest self…

Ryun with Jessica Kubzansky, opening night of Dawn’s Light

What about working with Jeanne and Jessica in shaping the production?

Jeanne Sakata had spent ten years writing the play. She had a mountain of research, but more than that she had her own experience of what her own relatives had been through in the camps. She would often return our focus to the truth of the experience. Jessica would continuously make it theatrical. We had a great harmony together. I would spend much time studying Gordon’s movements, the power of his bear-like hands, or putting myself into a time and place when I wouldn’t have been allowed to eat in a white restaurant, or swim in the pool. Jessica had the sure touch of someone who knows, blending all of these talents together effortlessly. Both she and Jeanne regarded the piece above their own individual egos. That is, for me, one of the most wonderful working environments there can be.

Ryun (tie-dyed t-shirt) in Sea Change

Most recently, you appeared in the LA Weekly Award-winning Sea Change. What were the challenges to you in creating your character, a gay man who eventually succumbs to AIDS?

Gene was so rooted in the 60s and the 80s. He was such a free spirit, and yet in so many ways so bound. Trying to understand the societal pressures on him took some time, but the biggest thing was trying to honor him. He seemed to me one of those people I like the best. Someone who shines so brightly in this world, someone who has a lot of love, the kind of person that when they go, the world seems darker.

What effect did being part of this production have on you as an actor and as a man?

I guess I feel that there is a little of Gene in all of us.

Sea Change was a perfect example of colorblind casting. There was no reason for your character to be Asian, yet every reason for you to be cast in the role, simply because of the talent you’d bring to the part. Why don’t casting people think more often “outside the box,” and can anything be done to change this?

I find there are very few people who are able to push borders. It takes a lot more work. I think it is ultimately what sets apart the innovators and the leaders of the pack from the others. I don’t think that will change. I don’t think we can look to casting directors or producers to change this. I think we need to create work for ourselves that can be financially successful. Once we demonstrate our faces are commercial, people will be more willing to cast us.

Speaking of casting “outside the box,” you’re about to star in Yasmina Reza’s Tony Award-winning Art. I can’t recall another major L.A. production of the play, so I’m really looking forward to seeing it. Can you tell me something about your role?

I’m playing Ivan, a guy who gets put upon a lot. I just loved him when I read him—I thought his situation was so clear and universal. He’s getting married in two weeks and just trying to keep his two friends from destroying each other so that they can still be his groomsmen at his wedding.

What attracted you to it and the play when you heard that it was going to open the 2009-10 East West Player’s season?

The play is so well written. Alberto Isaac is a director I have known and respected for a while. We just don’t get that many chances to play great, well-written roles right now. It was like a great meal…

You’ve also accumulated an impressive number of film and TV roles over the past few years. What does working in film and TV bring you as an actor that stage work doesn’t?

There is an energy, attention, and prosperity attached to TV and film work. A different kind of food.

What kind of challenges do you face in Hollywood as an Asian American actor?

There are of course many challenges to being an ethnic actor—and especially being Asian… But I think the greatest challenges are from within. You must be confident. You must persevere. I think the greatest example of someone who has transcended race in a different field is, of course, Barack Obama. That wholeness that you can sense from him is amazing. I think generations ago, one of the things that people used to say about African-Americans was how they would sabotage themselves. How many gifts were wasted and left to leak away in the darkness because of inner doubt, self-hatred, and other demons? How many people who are minorities, or have “alternate” lifestyles, or are women in fields that traditionally do not accept women, have had to not only accept the ordinary burdens of a career, but the additional extraordinary burden of finding the wholeness inside themselves necessary to succeed in that career? If we can defeat these inner demons, we can do anything.

Not so long ago, you directed Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night for Lodestone. Is directing something you’d like to do more of?

I am absolutely planning to do more directing. I loved it.

What do you as an actor bring to the role of director that someone without an acting background doesn’t?

I feel that I am maybe a little less reverential and perhaps more pragmatically oriented to the process because I am an actor.

Speaking of Lodestone, I see that The Mikado Project, which I saw a few years ago on stage, is being turned into a movie! Can you talk a bit about the film and your role in it?

The film is directed by Chil Kong, one of the artistic directors of Lodestone Theater Ensemble, which, as you know, is in its last season this year. It is a love letter to that theater company, and a little bit of a goodbye. It is a comedy, it is a musical, and it has Tamlyn Tomita. I play Ben, an intensely insecure actor and worker at Home Depot who thinks he’s the heir to Brando and is desperately in love with Tamlyn’s character.

When can we expect to see The Mikado Project screened?

I don’t know when it will be done… We just shot some pickups for it a month ago—but I will make sure and let you know.

Thanks, Ryun, and thanks so much for taking time to answer our questions. I’m very much looking forward to being there for the Opening Night of Art, and seeing another Ryun Yu performance!

Want a glimpse at Ryun’s talent and versatility? Check out his demo reel.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY