Paula Vogel tackles pedophilia in her 1998 Pulitzer Prize-winning How I Learned To Drive, and if the sexual abuse of an eleven-(to seventeen)-year-old sounds like unpleasant subject matter for an evening of theater, you’re absolutely right. Told by its heroine Li’l Bit as a series of flashbacks, How I Learn To Drive is a play that had me squirming almost from its first moment. Notwithstanding, The Production Company’s current revival is as superbly performed, directed, and designed as they get.

Li’l Bit (Joanna Strapp) tells her tale from the point of view of a woman now in her mid-thirties, a survivor despite the scars left by her six-year relationship with her middle-aged (but thankfully not blood) Uncle Peck (David Youse). In a series of driving lessons (both actual and metaphorical), the audience experiences the seduction of a prepubescent girl as Li’l Bit herself did, though the reverse-chronological order of the play’s events means that it’s not till near the end of the play that we witness the decisive moment when Peck fondles his eleven-year-old niece for the first time.

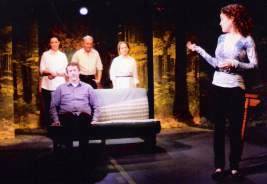

Li’l Bit’s family members are portrayed by a “Greek Chorus” of three. Male Greek Chorus (Skip Pipo) plays Li’l Bit’s grandpa, Female Chorus (Jennifer Sorenson) is her Mother, and in an interesting twist, Teenage Greek Chorus (fifteen-year-old Allie Grant) plays Li’l Bit’s grandma. The three actors also play high school students, a waiter, Li’l Bit’s Aunt Mary, and the voice of Li’l Bit at eleven.

Director August Viverito’s staging is stunning. An example: Our first encounter with seventeen-year-old Li’l Bit and Uncle Peck takes place on the front seat of Peck’s car, the two characters seated side by side as Youse pantomimes undoing Li’l Bit’s bra, lifting her blouse and kneading her breasts while Strapp shows Li’l Bit’s conflicted reaction. There is no body contact, no nudity, only what our imagination provides.

Vogel loves metaphor, and in gorgeously performed (and entirely discomforting) monolog, Uncle Peck teaches Li’l Bit to fish, his description of a child’s reaction to a fish getting caught (i.e. molested) precisely what Li’l Bit herself experiences at his hands or perhaps what he himself may have experienced as an abused child. (“Now, reel, jerk, reel, jerk… Hook it—all right, not easy, reel and then rest—let it play… Oh, no, don’t cry, come on now… No, no, you’re just real sensitive.”) If you’re like me, this monolog will have you squirming in your seat, especially because Youse is so out-and-out brilliant in the character he creates.

There are extended conversations between Li’l Bit, her mother, and her grandmother about a girl’s deflowering and how much blood and pain it involves. There’s another long metaphorical sequence in which Uncle Peck instructs Li’l Bit in the fine art of driving. Both sequences had me highly uncomfortable, as perhaps Vogel intended, though this is nothing compared to eleven-year-old Li’l Bit’s very first driving lesson on the back roads of Carolina, “the last day I lived in my body.” The scene is tragic, heartwrenching, and very hard to watch.

A South Carolina accent can be dripping with honeyed Southern charm (think Andie McDowell) but it can also be creepy as all get out coming from Youse’s Uncle Peck. The actor is the kind of middle-aged sexy that can prove irresistible to a younger woman, but renders his scenes with a teenage and preteen Li’l Bit all the ickier once you realize what’s going on inside his head and inside his pants. Youse is no two-dimensional villain, however. He shows us exactly why this genial man has always been Li’l Bit’s favorite uncle, and in his eyes, we catch glimpses of the abused child he may well have been himself. It is masterful work.

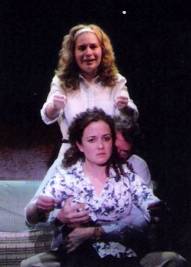

As Li’l Bit, Strapp proves herself one of our most gifted young actresses, giving easily the finest performance I’ve seen from her so far. Her Li’l Bit is instantly sympathetic, imbued with warmth and layers of pain, and when the young woman finally fights back at age eighteen, the scene is all the more powerful because Strapp has played eleven through seventeen so believably.

All three Greek Chorus members couldn’t be better. Pipo shines in a variety of roles, as Li’l Bit’s grandfather, as a waiter both judgmental about Peck’s ordering his teenage niece a total of three martinis and all too willing to serve them, as an eighteen-year-old student who gives adult Li’l Bit a taste of her own power as an older woman, and (walking on his knees), as a teenage schoolmate whose eyes come only up to the level of Li’l Bit’s already budding chest. Sorenson is excellent too, most particularly in a pair of monologs in which she advises Li’l Bit on how to drink as a lady should, getting drunker and drunker as she goes on to instruct her daughter in regurgitation techniques. Most impressive of all is Grant, who plays the daughter of Mary Louise Parker (the original off-Broadway Li’l Bit) on HBO’s Weeds. Vogel’s concept of having the Teenage Greek Chorus play Li’l Bit’s grandmother makes for some amusing moments, but it is Grant’s providing eleven-year-old Li’l Bit’s speaking voice during her very first sexual encounter with her uncle that provides the greatest proof of this young actress’s prodigious gifts.

Viverito’s direction is every bit at the same level as his Ovation Award-nominated work on last season’s Equus. His staging is visually imaginative, and no actors could do work as splendid as this cast’s without a master director at the helm. His set design once again does wonders with the Chandler Studio Theatre’s postage stamp of a stage. A wooded country road appears to be zooming past the car seat situated center stage. Add a table and the car seat becomes part of a dining room set. Lower the seatback and it doubles as a bed. Ric Zimmerman’s lighting is equally effective, as is Bob Blackburn’s sound design, with its medley of 60s hits, and the “ding” which introduces each of voice-over narrator Ed Brand’s “Driver Education” announcements which Vogel (a bit too cutely for my taste) uses to introduce each scene.

The ProdCo’s How I Learn To Drive is that rarity, a brilliantly staged production of a play I find myself unable to take to, in spite of its Pulitzer Prize pedigree. Despite my (in all likelihood) minority view of Vogel’s play itself, there is greatness in the work of Youse, Strapp, Viverito, and indeed of the entire company and crew. Vogel fans are sure to be raving about this one without reservations.

The Production Company, Chandler Studio Theatre, 12443 Chandler Blvd., North Hollywood.

www.theprodco.com

–Steven Stanley

January 22, 2010

Photos: Ric Zimmerman

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY