Where so-called “edgy” or “experimental” theater is concerned, the line between brilliant and pretentious is a fine one indeed, and in this reviewer’s experience at least, the latter is more often the case than the former. That’s why it’s such a pleasure to report that Theatre @ Boston Court’s production of Luis Alfaro’s Oedipus El Rey is out-and-out brilliant theater, even for playgoers whose tastes run, as mine do, more toward the traditional.

Alfaro has taken the ancient Greek legend and transported it to present day Latino L.A., more specifically to the barriocalled Pico-Union and to North Kern State Prison, where many of Oedipus El Rey’s characters have spent years of their lives. While Alfaro has taken certain liberties with the original plot, Oedipus El Rey is still very much a Greek tragedy, not just in its storyline but also in maintaining the Greek tradition of an onstage “chorus” who comment on the play’s events when not portraying various supporting characters. At times speaking in unison and at others as individuals, most frequently in English but occasionally in Spanish, this coro greco of five quickly establishes the production’s Latino identity.

In less proficient hands than Alfaro’s, Oedipus El Rey could have ended up un desastre pretencioso, i.e. a pretentious mess. Fortunately, with Alfaro’s often poetic words spoken by an absolutely superb ensemble under the brilliant direction of Jon Lawrence Rivera, Oedipus El Rey is simply theater at its finest, “experimental” or not.

As the five-man prison-uniformed coro take their places behind the cell block bars of John H. Binkley’s striking, angular set, Alfaro’s prologue establishes the play’s semi-bilingual nature from its opening lines. “Who is this man?” inquire the chorus. “¿Quién es este hombre? Who is this man who makes the prison library his home … who wants to be el rey? Lots of good it does him in here.” “In here” is North Kern State Prison, where we meet Oedipus’s adoptive father Tiresias, a counselor and seer slowly going blind.

A flashback then takes us twenty or so years back in time to the house in Pico-Union where Oedipus’s real parents, Laius and Jocasta, live. Laius, a king who wears his crown as a gold medallion hanging from a chain around his neck, arrives back home just as an oracle is attempting to read his unborn child’s future, the man’s hand placed on a pregnant Jocasta’s belly. The oracle has bad news for el rey. “That baby is going to kill you. You are cursed to be killed by your own son.” “Me va a matar,” repeats Laius, to which the oracle responds “Te lo prometo. I promise you.”

King Laius then goes to his servant Tiresias with news of the Oracle’s prophecy. “I have to kill my son,” el rey informs him, then issues an order regarding the newborn. “Take him to Griffith Park and hang him from a tree.”

The next thing you know, a grieving Jocasta, believing her son to have died in childbirth, is crying out “¡M’ijo! ¡M’ijo!” It is a grief from which she will never recover.

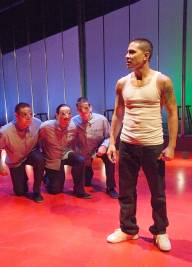

When next we meet Oedipus, the years have passed. The future rey is now a young man with a tattooed body grown rock hard from daily workouts, someone who has spent most of his life in reformatories and prison, raised as the only son of Tiresias, who disobeyed Laius’s orders, then later got himself arrested to be with his adopted son. Tiresias has told Oedipus only that his mother is dead.

One fateful day, Oedipus is visited by an oracle. In Alfaro and Rivera’s vision, the oracle is the five coro members wearing masks, circling around and around Oedipus as they prophesize that Oedipus’s father will die at his son’s hands. Thinking that they mean Tiresias, Oedipus expresses disbelief that he could ever hurt such a father. “I won’t kill him. He is my life. My breath.”

Meanwhile life goes on for Laius, who has become a violent, abusive husband to a demoralized Jocasta.

Upon his release from prison, Oedipus meets a man outside the penitentiary walls and asks him for a prophesy. “Go South,” replies the man. “To Pico-Union. Assume control of the kingdom.”

Just as happened to Oedipus in the ancient legend, Alfaro has the young man get into a fight with Laius over who owns the right of way on a narrow street. (Here though, both are driving cars, not chariots.) As in the legend, Laius refuses to back down, declaring that “I don’t think anyone with an ‘85 Honda Civic should be acting like he owns the road.” Laius threatens Oedipus with a return to prison, guaranteeing that with one phone call he could get the just released ex-con thrown back in jail like that.

With a strength that belies his smaller stature, Oedipus attacks the much larger man, and pummels him into submission. Just before Oedipus kills him with his bare hands, Laius cries out, “My son!”

Oedipus then meets Creon, a childhood friend from his years at the reformatory and asks his friend for a place to crash. “You can stay a week, tops,” responds a less than enthusiastic Creon, who lives with his widowed sister, none other than Oedipus’s still youthful mother Jocasta. “Don’t mention her old man,” cautions Creon. “That’s one of the things you shouldn’t talk about.”

From the moment Oedipus meets the tough, foul-mouthed widow, he feels a connection to this still young woman who keeps to herself, who is still punishing herself for whatever sins she feels she has committed. What is this force that draws him to Jocasta? Oedipus knows only that when he’s with her, it’s like a hole in him has just been filled.

Those familiar with the Greek legend need neither oracle nor review to foresee the fate that will befall Oedipus and his mother.

Besides playwright Alfaro’s talent at contemporizing a millennia-old tale in a milieu that effectively mirrors his own community, Oedipus El Rey succeeds because its characters and situations, however extraordinary, are absolutely real. So too are the performances director Rivera has elicited from his stellar cast.

Justin Huen is an absolutely stunning Oedipus, un hombre tough as nails but with a voice which reveals an inner gentleness, and his is a performance that only grows in strength and depth as his involvement with Jocasta deepens. Though her role is smaller, Marlene Forte matches Huen every step of the way as his mother/lover. The couple’s scenes together are positively electric, whether compelled by passion to remove every stitch of each other’s clothing or by destiny to the play’s climactic scene that had me literally shaking in my seat.

Winston J. Rocha does truly touching work as Tiresias and Leandro Cano is frighteningly real and menacing as Laius. The duo, joined by the equally excellent Carlos Acuña (El Sobador), Daniel Chacón (Creon), and Michael Uribes (Esfinge), make up the play’s five-inmate coro, whose work together is a rhythmic marvel of precision and power.

Oedipus El Rey is not all dark drama. Alfaro punctuates his script with flashes of humor, as for example when a pregnant Jocasta talks to her unborn child while watching … All My Children. Audience members who understand Spanish will laugh more often and get a bit more out of the play than those who don’t, but a glossary is included in the program, and my guess is that even those who don’t speak a word of español will find the play equally powerful and entertaining.

Besides Binkley’s arresting set, Theatre @ Boston Court’s design team has come up with one of the finest design packages of the year. Jeremy Pivick’s lighting is especially dramatic, making great use of color (red in particular) and geometric shapes. Dori Quan’s excellent costumes range from prison drab to Jocasta’s clingy dresses. Edgar Landa has choreographed one of the most exciting, violent, realistic fist fights I’ve seen on stage. As for Robert Oriol’s sound design (which includes his pulsating original music), it is truly in a class by itself, upping the drama and suspense at every turn. Jaclyn Kalkhurst serves as production stage manager.

Theatre @ Boston Court has a reputation for producing some of the edgiest theater in town. Occasionally that can betoo edgy for this reviewer. Not this time. Oedipus El Rey is a production that is likely to earn raves from everyone from the youngest, farthest-out theatergoer to the older, more traditional matinee set. People will be talking about this one. In fact, I’ll bet they already are.

Theatre at Boston Court, 70 N. Mentor Ave., Pasadena.

www.bostoncourt.org

–Steven Stanley

March 7, 2010

Photos: Ed Krieger

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY