Arthur Miller’s All My Sons is my very favorite 20th Century play, one I have now had the good fortune of seeing staged a half-dozen times. Debuting on Broadway less than two years after World War II ended with Japan’s surrender, Miller’s examination of personal responsibility in time of war remains every bit as powerful—and relevant— today, sixty-three years after its New York premiere.

This absolutely brilliant piece of writing has made a welcome return to the Southland in a production at Santa Monica’s Ruskin Group Theatre that is about as fine as they come, blessed by the inspired direction of Edward Edwards, brilliant lead performances, and splendid supporting turns all around.

The 1947 Tony Award winner revolves around a day in the life of the Kellers, a Midwest family who seem from the outside to be living the American Dream. At curtain up, prosperous factory owner Joe Keller (Paul Linke), his wife Kate (Catherine Telford), and their adult son Chris (Dominic Comperatore) are welcoming a visit from grown up next door neighbor Ann Deever (Austin Highsmith), back in town for the first time since moving to New York several years earlier. Ann and the Kellers’ older son Larry were an item when Larry went off to war, but the elder Keller boy was declared missing in action three years ago, and there has been no word of his fate. Though Kate steadfastly refuses to believe that Larry is dead, Ann apparently feels quite differently about the matter. She and Chris have been corresponding secretly for the past two years, and Ann’s return home signals a change in their relationship. Friendship has turned to long distance love, and Chris is planning to propose to Ann. There’s only one hitch. An engagement between Chris and Ann would mean a tacit acceptance of Larry’s death, and this is something which Kate will never do.

There’s one other stumbling block to the young couple’s potential happiness together. Ann’s father (and Joe’s business partner) Steve was sentenced to prison three years earlier for having knowingly sent out a shipment of defective airplane parts from Joe’s and his factory, cracked cylinder heads which led to the deaths of twenty-one pilots. Joe had initially been found guilty as well, however his insistence that he was home sick in bed the day the order got shipped out, corroborated by Kate, soon relieved him of any responsibility for the plane crashes, and he was subsequently released from prison.

When Ann’s brother George (Maury Sterling) shows up on the Kellers’ doorstep following a prison visit with his father, the stage is set for a two-family showdown which will forever alter the path of Chris Keller’s life and the lives of those he loves.

All My Sons works brilliantly on many levels—as a story of family, as a love story, as a mystery, and as a discussion starter. Even more than six decades after its premiere, All My Sons’ questions still ring true. Does a person’s responsibility to his family trump his responsibility to his country? Does war bring out the worst in people, or their best? Can a person go on living without self respect or the respect of others?

As its secrets are revealed, All My Sons becomes steadily more engrossing. Expect to gasp. Expect to cry. Expect to be moved profoundly by this truly great work of American theater—particularly in its intimate Ruskin Theatre setting.

Roberta Christensen’s excellent scenic design scales down the Keller home (facade, porch, and front yard) to fit the tight spaces of the Ruskin stage, successfully meeting the challenge of a theater which seats its audience on two adjoining sides. This L-shaped configuration combined with the Ruskin’s very intimate dimensions means that actors are often quite literally within touching distance of the audience—and director Edwards has his cast act accordingly, scaling down their performances to film-like subtlety. A larger house would cry out for bigger, stagier work. Here, less is absolutely right.

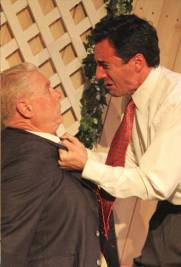

In Joe Keller, Linke gets one of the greatest roles ever written for an over-60 actor, a 20th Century Lear, and the stage/TV/film vet brings him to life as superbly as I’ve seen the part played. Linke makes you believe that this is a man who dropped out of school young, pulled himself up by his bootstraps, and succeeded through smarts, not education. As Joe’s secrets are revealed one by one, Linke’s performance grows in intensity and power in inverse proportion to the downward spiral of a life is falling to pieces.

Comperatore’s Chris may be more introverted and introspective than others I’ve seen, but the broodingly intense actor is no less effective for holding back, making Chris’s eventual sense of betrayal and his ensuing rage all the more devastating. Telford’s Kate too starts out relatively low-key, but from the beginning you sense the steel at her core, the actress’s work the very definition of multi-leveled. (Just wait till she lets out Kate’s fire within.) Highsmith combines beauty and acting chops in equal measure (think a young Michelle Pfeiffer), with a particular talent for listening … and being “in the moment.” Sterling makes for an excellent George, keeping his character’s intensity and anger nicely under control, though perhaps he could allow George to let down his guard a bit more, however briefly, once Kate has brought back those “home again” feelings.

Josh Drennen and Shae Kennedy do terrific work as Keller neighbors Dr. and Mrs. Jim Bayliss, Drennen giving us a man who has settled for so much less than his dreams and Kennedy adding some sly humor to Sue’s “get-out-of-town” confrontation with Ann. Understudy Chad Wood and Katie Parker are pitch-perfect as Frank and Lydia Lubey, whose interest in astrology fuels Kate’s hopes that Larry is still alive. (Almost)-10-year-old Tucker Riley does cute work as “Detective” Joe’s neighborhood helper Bert.

Christensen’s lighting design effectively complements her scenic design, with some particularly stunning fade-outs. Shelli Gonshorowski’s sound design incorporates 1940s tunes and appropriate sound effects. Matthew Perduis’s costumes have a nice period feel, despite the women’s seamless stockings. Hair and makeup also suggest the play’s 1947 timeframe. Tim Cox is stage manager.

Despite its mid-20th Century setting, Miller’s greatest play (and I say this recognizing that most would probably give the honor to Death Of A Salesman) remains quite possibly his most timeless, its issues of idealism versus pragmatism, and of responsibility to family and society, as relevant in 2010 as ever. Lovers of great theater, brilliant writing, and superb acting and direction need look no further than All My Sons at the Ruskin.

Ruskin Group Theatre, 3000 Airport Avenue, Santa Monica.

–Steven Stanley

August 21, 2010

Photos: Agnes Magyari

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY