If horse-blinder Alan Strang was a tough nut for psychiatrist Martin Dysart to crack in Peter Shaffer’s Equus, then the nameless Army Captain in Matthew Kellen Burgos’ engrossing new dramatic one-act After The Autumn proves an even greater challenge to the doctor assigned to his case.

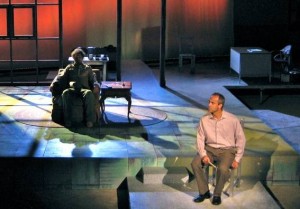

Now getting its World Premiere production by Vanguard Rep under the La Canada Flintridge stars, After The Autumn takes us on a non-linear journey, introducing us in flashback to the Doctor (Sam R. Ross), his patient (Clay Wilcox), two nurses (Alice McFarland and Adam Burch) charged with the Captain’s daily care, and the officer’s former subordinate (David Ross Paterson), as the actors recite from a redacted (i.e. heavily censored) report from the Doctor’s malpractice hearing. (We hear only beeps whenever a name is mentioned.)

The Captain’s day nurse fills us in on the facts. The officer has recently been transferred to the Ascension Military Recovery Clinic, “where they send the ‘ghosts,’” his symptoms including, “but not limited to insomnia, lasting depression, disturbing nightmares, difficulty in social settings, and anger management issues.” And if that weren’t already enough, the Captain appears virtually mute, that is except for outbursts of anger during which words emerge from his mouth that seem to make little or no sense.

We learn that the Doctor has been given the Captain’s case by the Medical Licensing Board as a probationary assignment to be fulfilled while attempting to recover from an addiction to sleeping pills and pain relievers. Should he not be able to kick the habit, the Doctor’s medical license will be permanently revoked.

In words eerily reminiscent of Dr. Dysart’s in Equus, the Doctor recalls his initial reaction to his troubled patient: “I have to get closer. Just a little closer. Just as I’m close enough to hear what he’s saying, suddenly his mouth opens wide. Impossibly wide. He screams with many voices all at once. God, the noise. Loud. So loud.”

As the Doctor begins his attempts at therapy, he discovers that the Captain has been so heavily sedated as to make communication virtually impossible. Vowing to wean his patient from his overprescribed meds, the Doctor is surprised one day when the Captain speaks words that seem far too formal for an Army officer. “Better be with the dead whom we, to gain our peace, have sent to peace,” begins the officer, “than on the torture of the mind to lie in restless ecstasy.” Though the words mean nothing to the man of medicine, the Captain’s night nurse recognizes them. “Crazy bastard’s rehearsing a one-man Macbeth.”

Somehow, the Doctor now realizes, the Captain is using the words and themes of Shakespeare’s Scottish Play to express some secret inner torment, and feeling inspired for the first time in a good long while, the Doctor vows to root out the cause of the Captain’s trauma before his patient is committed to spending the rest of his life as a sedated vegetable. What he does not initially realize is that this may mean uncovering secrets the military would do anything not to see made public.

Playwright Burgos takes considerable risks in having his Army Captain speak only in the words of Shakespeare, courting protests that something like this would never happen in real life. Still, as a theatrical conceit we go with it, particularly since Burgos has come up with that rarity, a World Premiere play which proves absolutely apt for a Shakespearean season. As for the performances director Burgos has elicited from his stellar cast, they simply could not be better.

Ross, Scenie winner for his Dramatic Performance Of The Year in Breaking The Code is utterly compelling as a man charged with healing a wounded soul, all the while dealing with inner demons virtually as relentless as those of his patient. Wilcox matches Ross every step of the way as the Captain, his eyes at once hollow and filled with pain, a shell of a man still possessed of the strength to do violence, though perhaps not enough strength to face life once again among the living.

The elegant Paterson disappears inside the Sergeant’s considerably coarser skin in a performance that transcends stereotype. McFarland gives the day nurse an Upper Midwest accent you could slice with a knife and layers of caring and warmth. Burch is terrific too as the night nurse with a junior college minor in theater and little tolerance for the Doctor’s efforts to save a patient he thinks would be best left to vegetate.

Ric Zimmerman’s lighting is as striking as Jason Knox’s sound design, with its censorship beeps and tape rewind whirs. Bethany Richards gets high marks for well chosen costumes. Elisa K. Blandford is stage manager.

Opening the evening is a brief performance piece, Tragic Women, adapted from Shakespeare by Ross, who directs it as well. The short one-act has the spirits of Ophelia (Eliza Kiss) and Desdemona (Kirstin A. Snyder) mentoring suicidal neophyte Juliet (Chelsea Taylor) entirely in words from Hamlet, Othello, and R+J. It features graceful choreography by Elizabeth Ross set to Nino Rota’s theme from Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo And Juliet. A worthy experiment, Tragic Women offers its three actresses the chance to do first rate work, with Kiss exhibiting a fine singing voice as well. Vocal arrangements are by Kathryn Gallagher and piano arrangement by Ben Coria. Richards costumes Tragic Women as well.

Still, the evening belongs to After The Autumn, a play that stands on its own and deserves future stagings. You will likely admire the imagination that went into Tragic Women, but it is the powerful After The Autumn that will stay with you long after the lights have dimmed.

Byrnes Amphitheater, Flintridge Sacred Heart Academy, 440 St. Katherine Dr., La Cañada Flintridge.

www.vanguardrep.com

–Steven Stanley

July 17, 2011

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY