RECOMMENDED

A formal invitation to a class reunion is but the first of dozens upon dozens of letters exchanged between the Assistant Director of Alumni Affairs at Prescott College and one of its most celebrated graduates, renowned author Joel Gordon, in Victor L. Cahn’s Roses In December, now playing at Beverly Hills’ Theatre 40.

That first invitation, and a second, and even a third provoke only a chilly rebuff from Gordon, but Carolyn is not to be deterred. A huge admirer of Gordon’s mammoth novel Shortcut To Oblivion, Carolyn has a more selfish reason for wishing to carry on a correspondence with her idol. As she eventually reveals to him, her plan is for a substantial part of her doctoral dissertation to revolve around Gordon’s novels and stories, and whatever personal insight he can offer her will be greatly appreciated.

Gordon informs Carolyn in no uncertain terms that hell will long have frozen over before he cooperates in any way, shape, or form with said dissertation, prompting Carolyn to undertake her own research, the result of which is the discovery of an unpublished Joel Gordon manuscript. That story, Roses In December, features a trio of protagonists bearing a striking similarity to Gordon and to Carolyn’s parents Paul and Alecia, whom the writer was friends with during his undergrad days at Prescott. Clearly, there is more to Gordon’s connection to Carolyn than initially meets the eye, and we begin to suspect that a surprise revelation or two might be in store, though for that, the playwright insists that his audience return after a brief intermission.

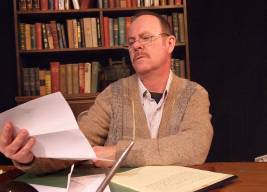

Like A.R. Gurney’s better known Love Letters, Roses In December features two characters whose only onstage interaction is through the letters they write, and we’re not talking emails or text messages, but rather good, old-fashioned paper-and-ink letters. Unlike Gurney’s Melissa Gardner and Andrew Makepeace Ladd III, however, Cahn’s Carolyn and Gordon have never met, and, we soon guess, seem unlikely ever to do so. Either way, an epistolary play creates problems, though fortunately director Melanie MacQueen and costars Amy Moorman and Lary Ohlson have gone a long way towards solving them.

The greatest problem is that a “play of letters” is by its very definition a series of monologs, soliloquies lacking the spontaneity and rapid-fire give-and-take of real-time face-to-face chats.

MacQueen’s solution to this is a smart one. Rather than take the easy route and simply have her two actors facing the audience several feet apart with script in hand (an approach that has allowed Love Letters to be performed innumerable times by innumerable duos attracted by the opportunity to act without need of memorization), MacQueen has her cast performing completely off book, each in his or her own furnished office at opposite sides of the Ruben Cordova stage. Even more importantly, the director allows us to observe simultaneously both writer and reader, thereby letting us see the immediate reaction of each of them to the other’s words, and giving each character stage business to attend to as the other reads aloud.

For this, MacQueen deserves considerable credit, the playwright having given her not a single stage direction from Carolyn’s first letter to Gordon’s last. Still, I couldn’t help wishing that the director had figured out a way to avoid keeping Carolyn entirely in her space and Gordon entirely in his. At the very least, the offices might have been flip-flopped at intermission, allowing audience members seated on either side of the wide Cordova stage proximity to both characters, at least for half of the play. (This reviewer, for example, saw Carolyn always at a distance.) Perhaps even better, a less literal staging would have allowed the actors to have freer range of the stage, to crisscross, to be at times in close proximity each to the other despite the distance separating the characters in “real life.”

Still, MacQueen and cast deserve a round of applause for making Roses In December, a wholly untheatrical script, as theatrical an experience as it is.

Moorman is striking in a patrician, Kennedy-esque way, and delivers her lines with poise and grace. Still, I would have liked to see and hear a greater variety of notes being hit, and to feel less that we are hearing letters being read. (In Moorman’s defense, Carolyn’s epistles tend to be more formal and studied than Gordon’s.) Ohlson has the advantage of his character’s explosive nature, which makes it easier for him to hit a broader spectrum of emotions. Also, the more off-the-cuff nature of Gordon’s rapidly scribbled letters allows the actor a greater conversationality. Still, it would probably take a Julianne Moore opposite a Jack Nicholson to truly make Roses In December catch fire—it’s that tough an acting challenge.

Jeff G. Rack’s set design is basically New England office furniture against a stark background I wish were something other than a plain black curtain. Fortunately, Ellen Monocroussos’s lighting design perks things up greatly, as do sound designer Bill Froggatt’s effectively chosen snippets of piano music between scenes. Michèle Young has designed a couple of outfits for each character that are just what I imagine each would have selected for him or herself. Michael Frank is stage manager. Roses In December is produced by David Hunt Stafford.

Ultimately, what impresses most is just how well Roses In December does work, despite a format more suited to the printed page than a theater stage. Playwright Cahn creates considerable suspense, and a touching, ironic finale that might just coax a tear or two from playgoers willing to go on this rather unorthodox theatrical journey.

Theatre 40, 241 S. Moreno Dr., Beverly Hills.

www.Theatre40.org

–Steven Stanley

December 8, 2011

Photos: Ed Krieger

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

Since 2007, Steven Stanley's StageSceneLA.com has spotlighted the best in Southern California theater via reviews, interviews, and its annual StageSceneLA Scenies.

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY

COPYRIGHT 2024 STEVEN STANLEY :: DESIGN BY